It took solely twenty-five years from the time that “Compensation,” Zeinabu irene Davis’s first fiction characteristic, premièred at Sundance to the time, this coming Friday, that it will get its theatrical launch. Many movies have languished in undue obscurity due to obtuse opinions after they have been first screened. “Compensation,” nonetheless, obtained a number of enthusiastic ones out of Sundance (together with from Roger Ebert, in the Chicago Sun-Times), but a evaluate in Selection, as if hooked on Hollywood varnish, damned it as “imaginatively conceived however indifferently executed” and condemned it to the “noncommercial” realm. It was a nasty time for the releasing of impartial and worldwide movies basically, and “Compensation” was among the many finest movies to stay within the shadows till it resurfaced, a decade in the past, at particular screenings, for a extra receptive technology of viewers and trade individuals alike.

I first noticed it in 2017, when it screened at MOMA; first reviewed it in 2019, when it performed at BAM; and have been writing about it each likelihood that I get, as a result of it’s a many-faceted movie that, within the span of a mere hour and a half, retains revealing wonders. Like most nice films, “Compensation” expands the probabilities of the cinema, and my belated viewing of it provided the uncanny feeling of a vicarious reminiscence—of an expertise that I’d by no means had however that immediately felt like part of my very own previous, a lacking one which had simply been stuffed in. Now, rewatching the film, in a brand new digital restoration (or, as Davis calls it, a “rejuvenation”), I latched on to facets of it that, although all the time plainly current, now strike me as decisive: its framework, its kind. Nonetheless elaborate a murals could also be, the essence of genius is simplicity, and with “Compensation” Davis turns the inherent difficulties of a low-budget manufacturing right into a spare and clear kind, which proves to be extra capacious than that of most high-budget spectacles. That kind inflects the whole film—the contours of its dramas, the fashion of the performances, the earnest emotionalism—whereas additionally embodying a noteworthy conceptual imaginative and prescient. The result’s as intimate as it’s summary, as analytical as it’s lyrical; Davis fuses a mode of swish candor with a super of historic scope.

“Compensation” presents two parallel, intercut tales which are linked dramatically and thematically, and which, between them, body the 20 th century. One is ready round 1993 (when the filming started), and the opposite is ready in and simply after 1906. Each tales are set in Chicago, within the Black group, and each contain a romantic relationship between a deaf girl and a listening to man. Within the historic one, Malindy Brown (Michelle A. Banks), an mental and an activist who works as a seamstress, meets a laborer named Arthur Jones (John Earl Jelks); the fashionable one presents the connection of Malaika Brown (additionally performed by Banks), a printer and an aspiring graphic artist, and Nico Jones (Jelks), a youngsters’s librarian. In each tales, the very chance of a relationship relies on the person studying American Signal Language. (Malindy teaches Arthur whereas additionally educating him to learn and write; Nico learns A.S.L. by attending courses.) In each, the connection is seen skeptically by the lady’s circle: Malindy’s mom questions her bond with an uneducated man; a pal of Malaika’s challenges her reference to a listening to individual. In each, Black tradition performs a outstanding function, beginning with a poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar from which the movie will get its title. And, in each, epidemic ailments get in the way in which. (It’s no spoiler to notice that Dunbar’s poem, which is displayed onscreen in a title card earlier than the motion begins, ends with the phrase “demise.”)

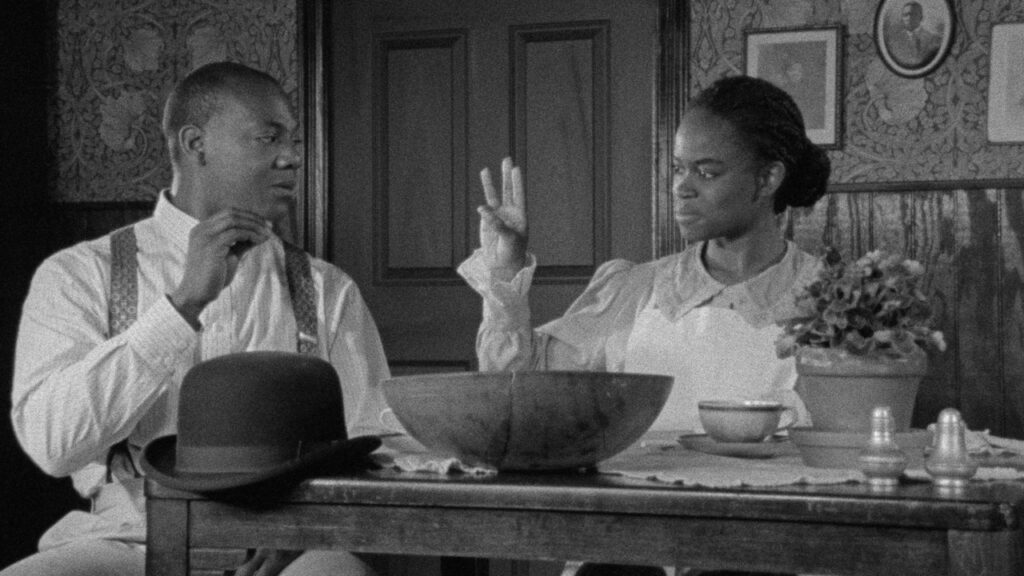

The tales and the themes of “Compensation” come to life by a set of extraordinary units whose aptness, as with all nice discoveries, appears logically inevitable as soon as it’s been completed. As a result of films of the nineteen-aughts have been silent, Davis tells the story of Malindy and Arthur as a silent movie, full with intertitles for dialogue and narration. But she indicators the idiosyncrasy of this selection by including a soundtrack that, whereas it lacks speech, consists of some sound results, as if to name consideration to the essential absence of spoken dialogue. (There’s additionally copious piano music, a lot of it ragtime, composed and performed by Reginald R. Robinson—evoking accompaniments to film screening within the silent period.) The silent film can be a reconstitution of a long-ago world, and it’s as exact as it’s expressive: Davis depends on evocative outside areas (parks, seashores, outdated homes) to depict the general public realm. For indoor settings, such because the neat, snug room the place Malindy lives, Davis’s manufacturing design is modest and expressive. Reasonably ornamented furnishings, white cloths and lace curtains, vigorous wallpaper above plain wainscoting, and a spare however formal array of glassware conjure the period in eye-catching touches—as do Malindy’s flowing clothes, straw hat, and velvet finery, and Arthur’s suspenders, high-waisted pants, tab collars, and bowler hat. Davis’s easy but cannily composed photos (because of cinematography by Pierre H. L. Désir) really feel recovered from the previous; of their concentrated poise, they let materials particulars sing.

Davis’s prime gadget for depicting the previous and for bringing Malindy and Arthur’s world to life relies on a wealth of archival pictures, and it’s one which dangers being misunderstood if not clearly named: “Compensation” is, partially, a documentary. All through, Davis weaves into the motion a personally curated archive, rendered important and quick by her cinematic remedy. The digicam strikes throughout the images in a manner that creates a kind of montage: zooming in on particulars, increasing outward to disclose panoramic views, and bringing real-life individuals into closeups so joltingly expressive that they appear like actors within the drama. The film opens with such a documentary sequence, a historical past lesson of the Nice Migration: pictures set up the doubling of Chicago’s Black inhabitants from 1900 to 1910 and a few landmarks of tradition that went with it, such because the publication of W. E. B. Du Bois’s “The Souls of Black Folk” and of Scott Joplin’s opera “Treemonisha.” Not one of the film’s dramatic characters are launched till this elaborate first sequence runs its course.

The mass motion of the Nice Migration is seen in archival photos of prepare journeys by rural fields the place Black individuals do farm work and in photos of the turmoil and vitality of the commercial metropolis. Within the ideally suited of “schooling, employment, enlightenment” provided by metropolis life, Davis exhibits city Black businesspeople and artisans at their trades. When Malindy is launched, Davis provides {a photograph} of an built-in faculty for the deaf from the late nineteenth century, such because the one Malindy attended, in Mississippi. (Her faculty changing into segregated, in 1906, is what made her transfer to Chicago.) Introducing Arthur’s work as a meatcutter within the meatpacking vegetation abutting Chicago’s stockyards, Davis provides historic photos of the stockyards that vividly conjure the laborious and harmful work, seemingly even the stench. What emerges in these nonfiction segments isn’t the amount of the analysis however its depth—a way of discovery within the archives to equal the sense of discovery that emerges from the on-set performances, which have the joys of quick creation.

There’s simply as a lot documentary woven into the overtly fictional sequences—for starters, the documentation of cultural historical past. Malindy’s story entails the poems of Dunbar, the journal The Disaster (based by Du Bois and printed by the N.A.A.C.P.), the journalistic activism of Ida B. Wells (to whom Malindy writes concerning the segregation of her faculty), the Black opera singer Sissieretta Jones, and, particularly, Black cinema: films made by Black artists for Black viewers. Davis properties in on a real-life instance of this type, a brief comedy known as “The Railroad Porter,” which is now misplaced, and recreates it, in a scene the place Malindy, Arthur, and their mates go to the films. (Emblematically, that is the one scene within the 1906 story to characteristic spoken dialogue—the viewers speaking again to the display!)

Within the trendy story, Malaika, an artist, additionally dances (Banks is a choreographer and a dancer), and Dunbar’s poetry figures repeatedly in her story and Nico’s, too; the poem of the title, set to music, evokes a exceptional dance efficiency by Malaika’s pal Invoice (Christopher Smith). Malaika and Nico are each ardently concerned with African artwork and music and participate in Yoruba rituals. (The rating within the trendy part, used sparingly and strikingly, that includes percussion-based compositions and devices, is by Atiba Y. Jali.) Popular culture of the time additionally performs a task, as Malaika and Nico face a comical conundrum when attempting to choose a film at a neighborhood multiplex.

There’s yet one more documentary ingredient on the heart of “Compensation”: deafness. The lives of the film’s two deaf girls, and their relationships within the talking world, are proven with a forthright engagement. For Davis, deafness isn’t a metaphor, it’s merely a lifestyle and a realm of expertise. (The restored model of the movie, because of new expertise, consists of much more onscreen captions for the hearing-impaired.) Certainly, the script, by Marc Arthur Chéry, who can be Davis’s husband, didn’t initially heart on deaf characters, however when the couple noticed a stage efficiency by Banks—who had based a theatre firm for deaf Black actors—Davis immediately determined to forged her, and adjusted the characters and the script accordingly. Each tales emphasize the centrality of A.S.L., its accessibility to listening to individuals as a second language, and—notably within the trendy story—a view of deaf tradition as a significant facet of tradition at massive. Within the trendy story, deaf tradition is much extra extensively developed. The ensuing paradox is that, as deaf tradition expands (however listening to individuals’s data of it hardly retains up), relationships between deaf individuals and listening to individuals turn out to be more and more fraught and tough.

The distinctive type of “Compensation” has an inherently didactic facet. In telling the cognate tales of Malindy and Malaika, Davis builds a mighty arc of time—a view of intimate life as inextricable from the nice forces of historical past, of romance as inseparable from cultural creation, of the current day tethered as tightly to the previous, as if the connection have been telepathic, metaphysical. Even the performances have an exemplary historic tenor. Banks and Jelks, as directed by Davis, supply a mix of fluid expression and strong reserve, of monumentality in intimacy, that has extra in frequent with the methods of basic Hollywood stars than with pliable trendy actors of practical bent. Though each actors distinguish their historic and trendy characters by the use of totally different tones of efficiency and totally different gesture repertories, the continuities are much more evident than the variations, which is, largely, the energizing concept of “Compensation.”

The nice energy of the film, past the passionate specifics of its romantic dramas, is within the distillation of an unlimited imaginative and prescient of historic unity. From nation to metropolis, tradition at massive into non-public life, the home sphere into the general public realm, the spiritual world to the secular one, the deaf to the listening to, from Africa to America, from author to reader and artist to viewer, Davis shows the relentless movement of communication, the transmission of experiences and concepts from individual to individual and from technology to technology. “Compensation” has the uncommon advantage of each depicting and embodying the non-public expertise of historical past’s continuous technique of rediscovery and reclamation. Loads of films, notably impartial ones, fall into the zone of oblivion on the time of their creation. Often, one in every of them could also be acknowledged belatedly as a masterwork that retroactively transforms the historical past of cinema and guides its future. “Compensation” is likely one of the few such movies to exemplify its personal future. ♦