The French thinker Simone Weil was a soul at odds with herself and with a world of affliction. The causes she espoused as a social activist and the religion she professed as a mystic had been pressing to her and, as she noticed it, to humanity. Little of her work was revealed in her lifetime, however since her dying, at thirty-four, in 1943, it has impressed an nearly cultlike following amongst readers who share her starvation for grace, and for what she referred to as “decreation”—deliverance from enthrallment to the self.

Eminent theologians have revered Weil (Paul Tillich, Thomas Merton, Pope Paul VI), and so have writers of the primary rank, particularly girls (Hannah Arendt, Ingeborg Bachmann, Anne Carson, Flannery O’Connor, Susan Sontag). Albert Camus hailed her as “the one nice spirit of our time.” T. S. Eliot credited her with a “genius akin to that of the saints.” However Weil herself may need objected to those consecrations as a type of “idolatry,” which she outlined as a misguided thirst for “absolute good.” Nothing is so absolute about her as the problem of parsing her contradictions. Her writing radiates a cosmic empathy that coexists, typically on the identical web page, with a pressure of intolerance blind to life’s tragicomedy. She resists any system that enslaves the person to a collective, however her personal imaginative and prescient of an enlightened society—the topic of her most well-known work, “The Want for Roots”—is an autocracy modelled on Plato’s Republic. Weil would gladly have died combating the Nazis. But whilst her Jewish household fled the Remaining Resolution, she condemned Judaism with what her biographer Francine du Plessix Grey justly calls “hysterical repugnance.”

It’s a conundrum of Weil’s biography that almost all primary human wants had been alien to her. She shrank from the contact of one other physique, and thought of her personal “disgusting.” She slept on the ground in an unheated room. For many of her life, she subsisted on a hunger weight loss program—in solidarity, she stated, with the world’s victims of warfare and famine. Excessive fasting has an extended historical past amongst feminine saints, although it was chastened by the Church as a sin of delight. Weil’s biographers have debated whether or not to name her “anorexic”; the psychiatrist Robert Coles prefers to see her as a “famished seeker.” In searching for transcendence from her mortal hungers, her extremity exerts a magnetic power: it has the facility each to captivate and to repel us.

Weil formulated her extremity succinctly in “Gravity and Grace,” an anthology of numinous aphorisms that’s broadly thought of her masterpiece: “Don’t enable your self to be imprisoned by any affection.” She insisted that her solitude was “ordained,” and that she needed to be “a stranger and an exile in relation to each human circle.” However a good friend who revealed “Gravity and Grace,” Gustave Thibon, instructed that she was fooling herself. She “was not indifferent from her detachment,” he stated.

A brand new assortment of household correspondence, “Simone Weil: A Life in Letters,” edited and annotated by Robert Chenavier and André A. Devaux, offers perspective to Thibon’s koan. Weil’s nicknames for her dad and mom, Bernard and Selma, are Biri and Mime, and she or he indicators one message “Your little woman who loves you with all her energy however pays no consideration to spelling misstakes.” She principally addresses her mom. Many of those missives are dashed-off notes from camp—a daughter assuaging a mom’s anxiousness about her welfare, or scolding her for it, or asking for cigarettes and occasional filters, or reporting cheerfully on a tour of Italy (“Very stunning, La Scala”), or threatening that she “received’t eat for 2 weeks” if Mime sends her a care package deal she hasn’t requested for. But they humanize Weil the icon by the actual fact of their banality, and by their poignant testimony to her umbilical dependence as a toddler who by no means actually left residence.

Weil’s mind navigated time and area with supreme self-sovereignty, however her physique lacked a steering wheel. She had abnormally small and clumsy palms. She suffered from crippling migraines and extreme myopia. She ran into furnishings as she crossed a room. She was devoid of frequent sense. Understanding how rash she was, and the way unfit for the hardships that she would courtroom—manufacturing unit labor and frontline fight, dangers that endangered the very individuals in whose identify she took them—the Weils grew to become helicopter dad and mom, ever poised to swoop down and rescue her.

Like many saints and revolutionaries, Weil was a toddler of privilege. She and her brother André, one of many twentieth century’s preëminent mathematicians, grew up in luxurious. Bernard was a profitable internist; Selma was an heiress. One is startled to be taught from the letters that Simone loved tennis and snowboarding. Regardless of her choice for hovels, she wasn’t a stranger to posh inns. She cherished the ocean, so the household usually summered on the seashore. They had been collectively in Portugal when she had her first mystical expertise and in Good when Hitler invaded Poland.

The plump, vivacious Madame Weil was the type of formidable homemaker whom my very own Jewish grandmother would have referred to as “an actual balabusta” (adopted by the reason that “you would eat off her ground”). Her germ phobia could have contaminated Simone along with her lifelong revulsion at bodily contact. The breath of strangers was fraught with peril, so Selma’s youngsters needed to trip the bus on its open higher deck even in winter and to dodge kisses from anybody however shut kin. Weil’s college good friend and first biographer, Simone Pétrement, makes a degree of praising Selma’s heat and her tireless efforts to mom everybody in her orbit, with an “capacity to arrange . . . so overpowering that one was tempted to undergo her.” However maybe her competence was so daunting that it discouraged Weil from cultivating any. In one in every of her letters, she asks Mime boil rice.

Simone had been such a sickly toddler that she wasn’t anticipated to outlive. As a toddler, she refused stable meals. At 5, she was a holy terror, “with an indescribable stubbornness neither her father nor I could make a dent in,” Selma instructed a good friend. That yr, maybe not by coincidence, André, who was eight, found arithmetic and disappeared into them. Simone worshipped him. He had taught her to learn as a shock for his or her father. They recited Racine collectively. Historic Greek grew to become their secret language. (They used it to argue about Nietzsche.) After they misplaced their tempers, as siblings do, they mauled one another silently in a bed room, since raised voices upset their mom.

Selma had been forbidden to review drugs by an old style father, and she or he channelled her pissed off ambitions into educating her wunderkinds, hiring the perfect non-public tutors and enrolling her youngsters within the prime lycées. By twelve, André was working at a graduate degree and studying Homer within the authentic. At fourteen, he handed his baccalaureate, then sailed by the gruelling entrance examination for France’s most prestigious college, the École Normale Supérieure. Simone was one in every of solely two girls in her class on the Normale, and completed first on the examination basically philosophy and logic, with one other well-known Simone—de Beauvoir, a equally prodigious grind—proper behind her. However André was an authorized genius, and she or he by no means felt equal to him. On the onset of puberty, and of the migraines and depressions that subsequently plagued her, she “severely considered dying,” she wrote, as a result of “the extraordinary items of my brother, who had a childhood and a youth akin to Pascal’s, introduced my very own inferiority residence to me.”

It wasn’t solely her brother’s thoughts that Simone envied. She chafed at her project to the second intercourse, and wished nothing to do with femininity. Selma was admirably sympathetic. “I do my finest,” she instructed a good friend, “to encourage in Simone not the simpering graces of slightly woman, however the forthrightness of a boy even when it should appear impolite.” Each dad and mom referred to their youthful baby, at “his” request, as “our son quantity two,” and she or he used the masculine type of French participles in her scholar letters to them, which she signed “Simon.”

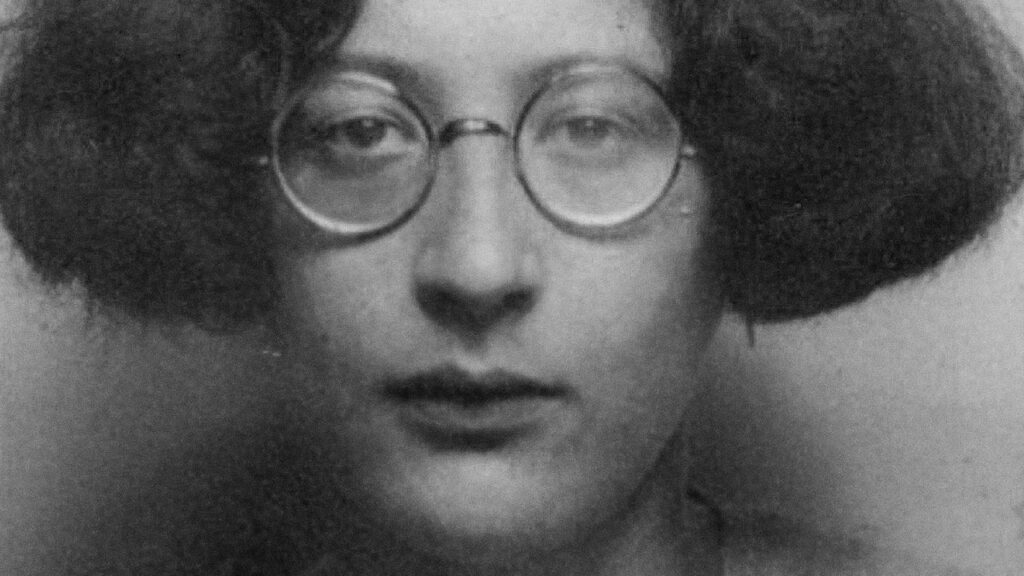

Past the sanctuary of residence, nonetheless, Weil was perceived as a freak, particularly by male contemporaries, who took her indifference to charming them as an affront to their masculinity. Her manners had been brusque to the purpose of surliness, and her tactlessness was legendary. In an period when public cross-dressing was unlawful for girls, she typically wore what appears like a mechanic’s jumpsuit, although her commonplace uniform was a grubby military-style greatcoat and a workman’s beret. The principal of the Normale referred to as her the Crimson Virgin. Georges Bataille caricatured her in his novel “Le Bleu du Ciel”: “A woman of twenty-five, ugly and visibly soiled. . . . The quick, brittle, uncombed hair beneath her hat gave her crow’s wings on both aspect of her face. She had the large nostril of a thin Jewess with sallow pores and skin between the 2 wings and beneath her wire-rimmed glasses.” But the poet Jean Tortel, who met Weil years later in Marseilles, would seize a charisma that Bataille had missed:

Weil got here of age throughout the Despair, and her twenties had been a decade of militant engagements—first as a Marxist, then as a radical commerce unionist who taught Latin and French literature to staff, then as a pacifist so uncompromising that, till Hitler invaded France, she favored appeasing him. However she couldn’t resist the possibility to battle Fascism with a gun, so she enlisted within the Spanish Civil Warfare, whose atrocities on each side so disillusioned her that she would name revolution, not faith, the “opium of the individuals.” (Her transient misadventure combating Franco with the anarchist Durruti Column ended when she stumbled right into a pot of cooking oil and suffered third-degree burns. Had her dad and mom not been hovering close by to evacuate her, she may need died of gangrene.)

However the defining chapter of Weil’s life on the barricades was her stint as a blue-collar employee. In 1934, she talked a sympathetic manufacturing unit proprietor into hiring her incognito for his meeting line. It was the primary of three jobs as a cog within the machine which left her “damaged” mentally and bodily. (In between them, Biri and Mime took her to recuperate at a Swiss sanitarium.) As a gratuitous ordeal, this episode has an aura of efficiency artwork, and Weil knew, in fact, that she was solely “a professor gone slumming.” However it was additionally a profound conversion expertise. From then on, as Grey notes, there was a shift in her language. The Marxist catchword “oppression” was changed by “affliction,” a phrase from the E book of Job. “Affliction will not be a psychological state,” Weil wrote. “It’s a pulverization of the soul.” It “compels us to acknowledge as actual what we don’t suppose attainable.”

Weil’s newest biographer, Robert Zaretsky, reminds us that she, like Orwell, was the uncommon “voice on the left” to denounce Fascism and Communism “with the identical vehemence.” One of many Weils’ Paris residences was a duplex on the Left Financial institution whose higher ground Simone as soon as loaned to Trotsky for a clandestine assembly—a pretext for confronting him with Soviet ruthlessness. Within the subsequent room, her mom listened with alarm to the shouting. Trotsky was berating Weil for her “reactionary” individualism. (His spouse chuckled on the audacity of “this baby” who was “holding her personal” with the good man.)

The power to see what others couldn’t was a present of Weil’s supreme intelligence, and likewise in all probability of what Elizabeth Hardwick calls her “spectacular and in some ways exemplary abnormality.” Her piety was as idiosyncratic as her politics, and plenty of creeds attracted her: Buddhism, Stoicism, Spinoza’s notion that God is nature. She was particularly drawn to the Cathars, a medieval sect whose ascetic practices spoke to her personal quest for disembodiment, as did their martyrdom. (They had been annihilated within the fourteenth century.)