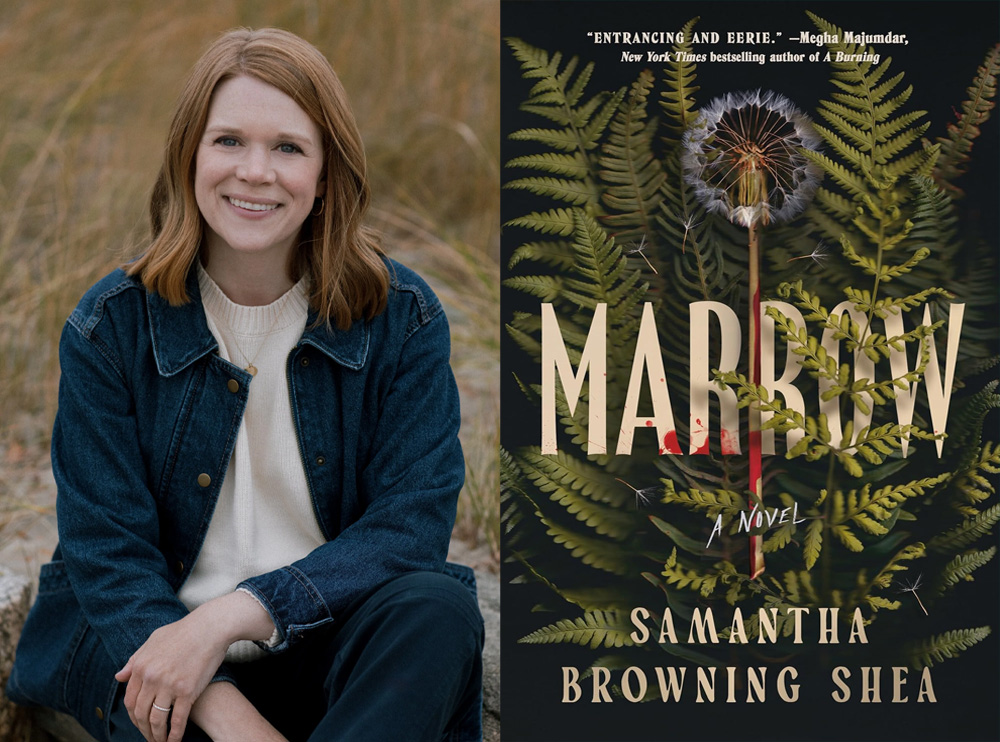

Visitor submit written by Marrow creator Samantha Browning Shea

Samantha Browning Shea is an creator and the vice chairman of Georges Borchardt, Inc. literary company. A graduate of Colgate College, Samantha lives in Connecticut along with her husband and their two daughters. Marrow is her debut novel.

About Marrow (out September ninth 2025): A searing tackle femininity and energy, Marrow transports readers to a small island off the coast of Maine, the place a coven has completed the seemingly inconceivable.

Once I was seventeen, I grew to become fixated on a TLC present known as A Child Story. It was the sort of present that slotted simply into the tv ecosystem of the early aughts, which was formed by comfortable voyeurism and the commodification of non-public transformation. In thirty minutes, the present moved with uncanny effectivity from being pregnant announcement to crying toddler, from a girl’s title to her new title: Mother.

On the time, I watched A Child Story the way in which one other teenager may watch porn – secretly, obsessively, virtually religiously. Not as a result of I needed kids. Not even as a result of I needed to grow to be a mom. I watched as a result of the present supplied one thing that, looking back, I used to be desperately trying to find: a story blueprint for turning into a girl.

The premise was easy, trite even. A lady, often in her late twenties or early thirties, navigates her third trimester in entrance of the digital camera. She is framed by comfortable lighting, her stomach spherical and agency. She outlets for a stroller. She debates “pure” childbirth. She makes an attempt the Lamaze-breathing we watched her be taught in a birthing class eleven minutes earlier than. There isn’t a narrative arc in addition to the organic one. Ache builds. It peaks. Then, launch. A child emerges. A lady is born.

I didn’t notice that what I used to be watching was not only a present about childbirth, however a present about id collapse. A lady enters the body as herself and exits it as one thing else, someone else – a mom.

In a media setting oversaturated with hyperfemininity, motherhood appeared like probably the most legible type of grown womanhood out there to me. A Child Story functioned as a soft-focus mythology builder. It offered motherhood not as an expertise, however as a sort of ethical horizon. In these tales, labor was a ceremony of passage, the physique a crucible, ache a vital precondition for turning into “actual.”

There was no mess. No postpartum despair. No local weather anxiousness. No ambivalence. It was, as a substitute, a fruits – a sort of punctuation mark on the finish of girlhood’s run-on sentence. The world that existed earlier than the infant was rendered peripheral, blurry, much less necessary. It was simple, at seventeen, to consider that this was aspirational somewhat than ideological.

Now, with distance – and with extra nuanced portrayals of womanhood out there to me – I see A Child Story as one of many earliest pop-cultural texts to usher me into the cult of motherhood: that refined however pervasive perception that to be totally feminine is to be selfless, giving, emptied out, each bodily and emotionally. The present’s most constant visible motif was the laboring lady: sweaty, primal, overcome. It was mesmerizing to observe her battle. And it was comforting to know that after the infant was born, the battle can be over. She had arrived.

However there isn’t any arrival, actually. And that fantasy – the concept womanhood is one thing you’ll be able to solely inhabit by means of struggling – damages the ladies who purchase into it. It warps their relationships with their very own our bodies and prepares them to equate love with ache.

I haven’t watched a full episode of A Child Story in years, although typically I nonetheless search for sure moms, the way in which different ladies of their late thirties may search for a childhood crush. I ponder in regards to the ladies, about what got here subsequent for them. I ponder in the event that they felt the type of transformation the present promised, or in the event that they felt like they misplaced one thing alongside the way in which.

Largely, I ponder in regards to the seventeen-year-old model of myself: hungry for path, visualizing my future by means of the grainy lens of TLC reruns, believing that probably the most transcendent model of myself would start in a hospital robe, with a contraction monitor beeping steadily beside me.

I don’t fault her. She needed to grow to be somebody complete. However now I perceive that womanhood doesn’t should be confirmed by means of ache. It doesn’t should be marked by a baby. It doesn’t should be earned.

Within the wake of the Dobbs determination, I can’t take into consideration A Child Story with out seeing it for what it additionally was: a soft-lit instrument of the patriarchy, quietly scripting ladies right into a imaginative and prescient of femininity that ends with self-sacrifice. The present marketed itself as a celebration, however in a post-Roe world, that framing feels much less like nostalgia and extra like prophecy – an early primer in how the tradition prepares ladies to provide themselves away, not simply willingly, however with gratitude.

It’s not that motherhood is inherently oppressive – because the mom of two younger daughters, I can attest that motherhood has additionally introduced me moments of unbelievable pleasure – however the fantasy that A Child Story supplied was by no means simply private. It was political. And for a technology of ladies raised on tales prefer it, we weren’t simply watching ladies grow to be moms. We have been watching them disappear.

I need extra for my ladies.