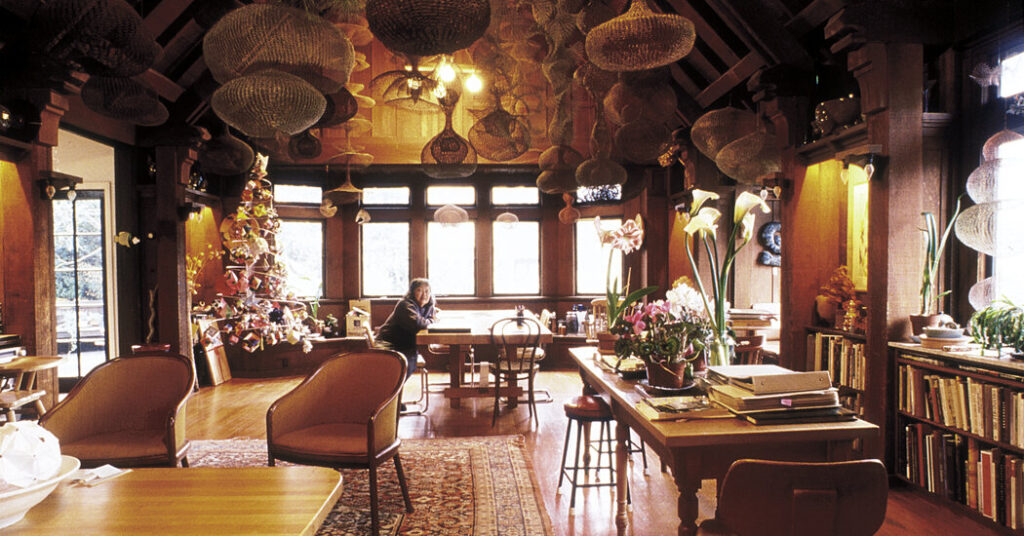

When you handed by way of the unlocked gate and rambling backyard into Ruth Asawa’s Noe Valley house between 1966 and 2000, the 5-foot-tall Japanese American artist would probably have persuaded you to lie down on the kitchen desk or front room flooring and let her cowl your face in plaster. Ethereal clusters of her undulating, looped-wire sculptures would have dangled from the rafters of the cathedral ceiling whereas her six kids, and later 10 grandchildren, ran underfoot.

“Ruthie might get individuals to do very weird issues — as a result of to have your face solid is a totally intimate act,” stated Addie Lanier, one among Asawa’s 5 surviving kids. Addie’s son, Henry Weverka, who additionally had his fingers and toes solid by his grandmother all through childhood, and now oversees her property, added, “She stated she appreciated capturing a second in time.”

Within the final 35 years of the twentieth century, impressed by a Life journal essay picturing Roman masks and busts, Asawa solid the faces of not less than 600 individuals. They included neighborhood kids in addition to her mentor, the visionary architect Buckminster Fuller, an influential instructor at Black Mountain Faculty in North Carolina within the late Nineteen Forties and to Albert Lanier, the 5-foot-8 structure pupil from Georgia whom she met and married whereas learning there. Asawa, who died in 2013 at age 87, hung her ever-expanding constellation of life masks on the ceder-shingled facade of their Arts & Crafts model house in a dramatically inclusive gesture of welcome.

“If she requested you to do one thing, nobody ever stated no,” stated Andrea Jepson, Asawa’s former neighbor who let the artist solid her entire physique shortly after giving beginning in 1967 because the mannequin for “Andrea,” a bronze mermaid fountain in San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square. Jepson recollects the home being “stuffed with different individuals on a regular basis. Nothing was compartmentalized.”