The expansive equipment of loss comprises many shifting components, interconnected tragedies that often develop into interconnected blessings. There may be the tragedy and blessing of time, which opens as much as the tragedy and blessing of reminiscence. I discover myself wandering by means of a type of prolonged wilderness of sound on mornings after I understand that my mom has been gone for thus lengthy that I can not clearly keep in mind her talking voice, solely a phrase or a half phrase surfacing in my thoughts earlier than the remaining tucks itself out of attain. The bewildering however fantastic blessing is that I do recall my mom’s singing voice, vividly, as one of many first sounds of my childhood. Whether or not or not somebody is a “good” singer, I feel, has to do partially with how a lot we love the particular person doing the singing, greater than it has to do with whether or not or not they’re an ample messenger for another person’s music, or an ample accompanist to a different voice spilling from a speaker. All of that is to say that I first encountered Roberta Flack’s music by means of the voice of my mom. I don’t keep in mind which music or songs, I simply keep in mind listening to my mom sing a music that was on the radio. My mom beloved Flack, and so I beloved her, and I used to be unhappy to listen to this week that Flack had died, on the age of eighty-eight, partially as a result of I knew that my mom can be unhappy.

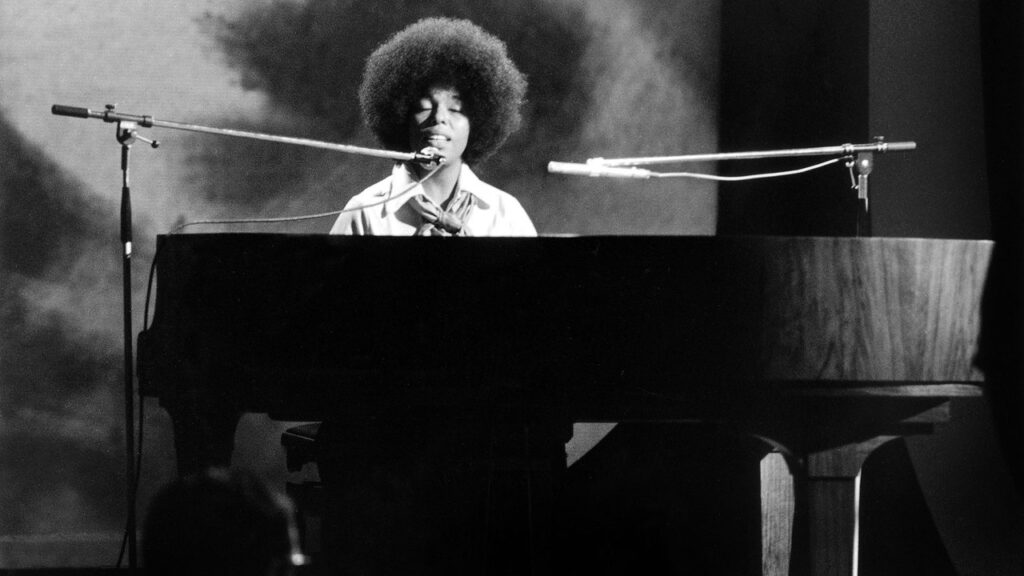

However I used to be additionally unhappy as a result of I first adored Flack as a translator of the feelings in somebody’s music—going above and past merely overlaying a tune to extract some new reserves of feeling, or narrative, or to sing it so effectively that her personal wishes coloured it anew. This capability was not totally stunning, given Flack’s musical background. She had sharpened her already formidable items at Mr. Henry’s jazz membership, in D.C., the place she had a residency in 1968. Folks would line up across the block to see her play a set listing that included covers and requirements. Flack’s début album, “First Take,” was recorded in simply ten hours in February of 1969, within the area between the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the summer time of Woodstock, and the cultural realignments that adopted. It’s my favourite Flack file, one that’s mournful, enraged, and continuously looking for. However I most like it for its transformations. The jazz customary “Ballad of the Unhappy Younger Males,” which closes the album, was written in 1959, by Tommy Wolf and Fran Landesman, for the musical “The Nervous Set,” a manufacturing centered on an avant-garde journal writer and his spouse, a Beat magnificence, and their dysfunctional marriage, which can’t be saved by the spoils New York Metropolis has to supply. “Ballad” is a sombre tune, regardless of who sings it, be it Tani Seitz, within the unique solid recording; or Shirley Bassey, singing it reside along with her arms wrapped round her shoulders as if she has, within the midst of her personal loneliness, been charged with protecting herself heat; or Rickie Lee Jones, whose vocals are half slurred across the gentle choosing of a guitar. Throughout Flack’s time educating music in D.C., within the years earlier than “First Take,” she would sing the music throughout performances that occurred 5 nights per week, thrice an evening, at Mr. Henry’s. Atlantic Data signed her to a file deal on the advice of the jazz musician Les McCann, who had seen her on the bar. Her efficiency of “Ballad of the Unhappy Younger Males” on “First Take” is very devastating for a way Flack dwells on the setting of scene. You must perceive a scene earlier than you perceive all of the ache that takes place inside it.

This was, to me, the superpower of Flack: her willingness not simply to take you to a sense however to first construct a spot to include it. Within the music, there are unhappy younger males, sure, sitting in bars. However it’s the method Flack takes her time with the verses of the music, every comprising only a few traces of lyric, that makes you perceive that these are unhappy younger males who’re looking for somebody and combating in opposition to time itself. They’re “rising outdated / that’s the cruelest half.” It’s, maybe, as a result of Flack had sung the music in a bar so regularly, and for thus lengthy, that she got here to grasp its engine to be much less “about” the ache echoing by means of the bar itself than about every part that carries somebody inside a bar. Loneliness could be the music’s wings, however loneliness, pressed in opposition to the brutalities of time, is what makes it take flight.

Talking of flight, Flack first heard “Killing Me Softly with His Tune” on a aircraft in 1972, when the unique, sung by Lori Lieberman, was featured on the in-flight audio program. Flack was so struck by the music’s title and by the music itself that she performed the music a number of instances throughout the aircraft trip, jotting down notes on the melody, and in two days’ time she had the association. Flack’s model, launched in 1973, is extra pressing, with a propulsive backbeat that helps the music construct towards its well-earned crescendo and its closure on a significant chord. The B-side of the “Killing Me Softly” single comprises Flack’s rendition of Bob Dylan’s “Simply Like a Girl,” which is one in all my favourite covers of any music within the historical past of songs, largely as a result of it finds a solution to overcome a cover-song pet peeve of mine, specifically, the tweaking of lyrics to go well with the gender of the singer. There was actually no different solution to finesse issues right here than to modify Dylan’s “she” to “I,” however the change has a unusually salutary impact. It affirms to the listener that, sure, Dylan might have been a considerably sympathetic spectator of the “she” in query, however that Flack is the actual deal, somebody carrying the burden of each witness and expertise.

On Sundays in Columbus, Ohio, after I was rising up, the Black radio station I listened to would abruptly shift at 6 P.M. from its all-day gospel to Quiet Storm Hours. The final notes of some music about God or heaven would fade away at five-fifty-nine, after which a cartoonish crash of thunder would come over the radio, adopted by the sound impact of rain hitting a window. I beloved the Quiet Storm’s lineup of jazzy R. & B. that was deeply emotive, intimate, tinged with romance or longing. Roberta Flack was the architect of this subgenre, which relied a lot on subtlety over anguished yelps, the romantics of plainspoken earnestness over hyperbolic metaphor or imagery. Flack would sing “Once you smile, I can see / that you just have been born, born for me” with a shrug, prefer it was one thing she’d say over a meal with a beloved, with out making a scene of it, prefer it was one thing value feeling and subsequently one thing value saying. I discovered her to be a singularly courageous romantic, a minimum of within the type of music. Sure, she was sensible in entrance of a piano; she was an excellent arranger and rearranger; she was a grasp of understanding tempo and momentum; she was additionally an ideal duet associate, most prominently reverse Donny Hathaway within the seventies, and Peabo Bryson within the eighties. However along with, and maybe past, all of that, she sang like she had been holding on to a secret that was ready to develop into yours. There was no have to shout it, as a result of the phrases would do the work on their very own. I sing Roberta Flack songs, poorly, in my bathe generally. I sing them—way more quietly, however nonetheless poorly—whereas navigating airports, which, for all their treacherous chaos, often supply me a glimpse of 1 particular person working into the arms of one other. Flack is my favourite singer to sing alongside to, as a result of she makes me not care whether or not or not I’m an ample vessel for the music. She invited a listener into the inside world of a sense, and it will be a betrayal for me to enter that place and never, a minimum of, by means of echoing her lyrics in a toilet or on a boarding line, say, Are you able to imagine this? ♦