Mars’s signature red hue may not be due to hematite, as previously believed, but rather to ferrihydrite — an iron oxide that requires water to form.

Using a combination of spacecraft data and laboratory experiments, researchers have provided the first solid proof that Mars rusted far earlier than expected, during a time when liquid water still shaped the planet. This discovery rewrites the timeline of Mars’s climate history and its potential for past habitability, setting the stage for future missions to uncover even more secrets.

Mars’s Red Hue: A Rusty Mystery

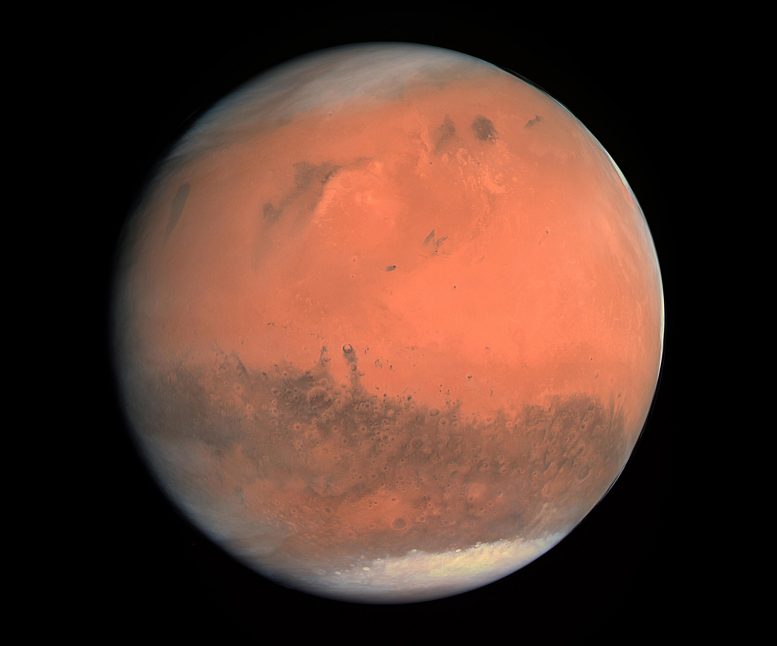

Mars stands out in the night sky with its distinctive red color. Decades of spacecraft observations have revealed that this hue comes from iron minerals in the planet’s dust that have rusted over time. Similar to how rust forms on Earth, iron in Mars’s rocks has reacted with water or a combination of water and oxygen in the air.

Over billions of years, this iron oxide has broken down into fine dust, which Martian winds continue to spread across the planet’s surface.

However, not all iron oxides are the same, and scientists have long debated the exact chemistry behind Mars’s rust. Understanding how it formed provides crucial insights into the planet’s past environment — and whether it was ever capable of supporting life.

Previous studies of the iron oxide component of the Martian dust based on spacecraft observations alone did not find evidence of water contained within it. Researchers had therefore concluded that this particular type of iron oxide must be hematite, formed under dry surface conditions through reactions with the Martian atmosphere over billions of years – after Mars’s early wet period.

New Findings Challenge Previous Assumptions

However, new analysis of spacecraft observations in combination with novel laboratory techniques shows that Mars’s red color is better matched by iron oxides containing water, known as ferrihydrite. Ferrihydrite typically forms quickly in the presence of cool water, and so must have formed when Mars still had water on its surface. The ferrihydrite has kept its watery signature to the present day, despite being ground down and spread around the planet since its formation.

“We were trying to create a replica of martian dust in the laboratory using different types of iron oxide. We found that ferrihydrite mixed with basalt, a volcanic rock, best fits the minerals seen by spacecraft at Mars,” says lead author Adomas Valantinas, a postdoc at Brown University in the US, formerly at the University of Bern in Switzerland where he started his work with ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) data.

“Mars is still the Red Planet. It’s just that our understanding of why Mars is red has been transformed. The major implication is that because ferrihydrite could only have formed when water was still present on the surface, Mars rusted earlier than we previously thought. Moreover, the ferrihydrite remains stable under present-day conditions on Mars.”

A Comprehensive Proof for Ferrihydrite

Other studies have also suggested ferrihydrite might be present in Martian dust, but Adomas and colleagues have provided the first comprehensive proof through the unique combination of space mission data and novel laboratory experiments.

They created the replica Martian dust using an advanced grinder machine to achieve the realistic dust grain size equivalent to 1/100th of a human hair. They then analyzed their samples using the same techniques as orbiting spacecraft in order to make a direct comparison, finally identifying ferrihydrite as the best match.

“This study is the result of the complementary datasets from the fleet of international missions exploring Mars from orbit and at ground level,” says Colin Wilson, ESA’s TGO and Mars Express project scientist.

Mars Express’s analysis of the dust’s mineralogy helped show that even highly dusty regions of the planet contain water-rich minerals. And thanks to TGO’s unique orbit that allows it to see the same region under different illumination conditions and angles, the team could disentangle particle size and composition, essential for recreating the correct dust size in the lab.

Data from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, together with ground-based measurements from NASA Mars rovers Curiosity, Pathfinder and Opportunity, also helped make the case for ferrihydrite.

Future Missions to Uncover More Clues

“We eagerly await the results from upcoming missions like ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover and the NASA-ESA Mars Sample Return, which will allow us to probe deeper into what makes Mars red,” adds Colin.

“Some of the samples already collected by NASA’s Perseverance rover and awaiting return to Earth include dust; once we get these precious samples into the lab, we’ll be able to measure exactly how much ferrihydrite the dust contains, and what this means for our understanding of the history of water – and the possibility for life – on Mars.”

For a little while longer, though, Mars’s red hue will continue to be admired and puzzled over from afar.

Reference: “Detection of ferrihydrite in Martian red dust records ancient cold and wet conditions on Mars” by Adomas Valantinas, John F. Mustard, Vincent Chevrier, Nicolas Mangold, Janice L. Bishop, Antoine Pommerol, Pierre Beck, Olivier Poch, Daniel M. Applin, Edward A. Cloutis, Takahiro Hiroi, Kevin Robertson, Sebastian Pérez-López, Rafael Ottersberg, Geronimo L. Villanueva, Aurélien Stcherbinine, Manish R. Patel and Nicolas Thomas, 25 February 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-56970-z