E-book Evaluation

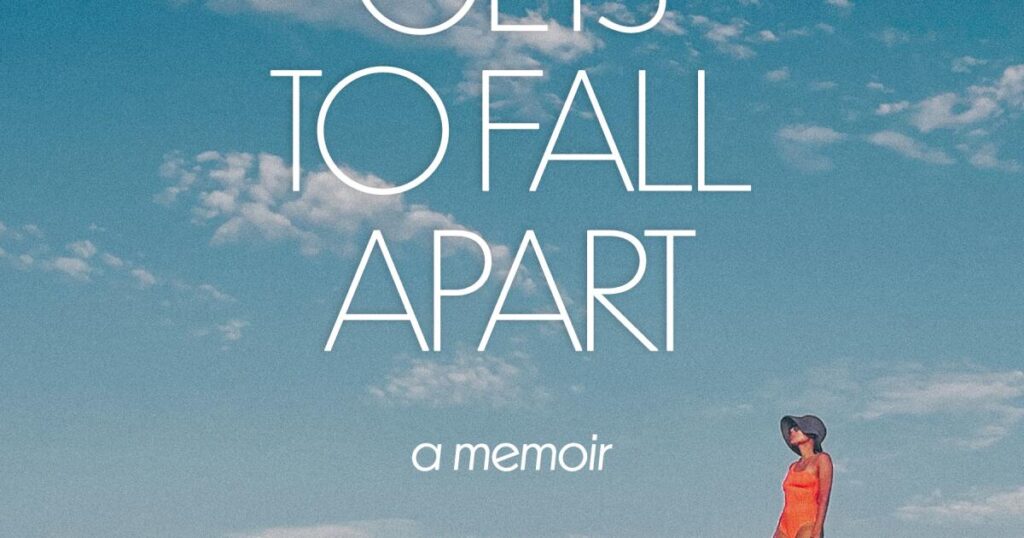

No One Will get to Fall Aside: A Memoir

By Sarah LaBrie

Harper: 224 pages, $27.99

Should you buy books linked on our web site, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist impartial bookstores.

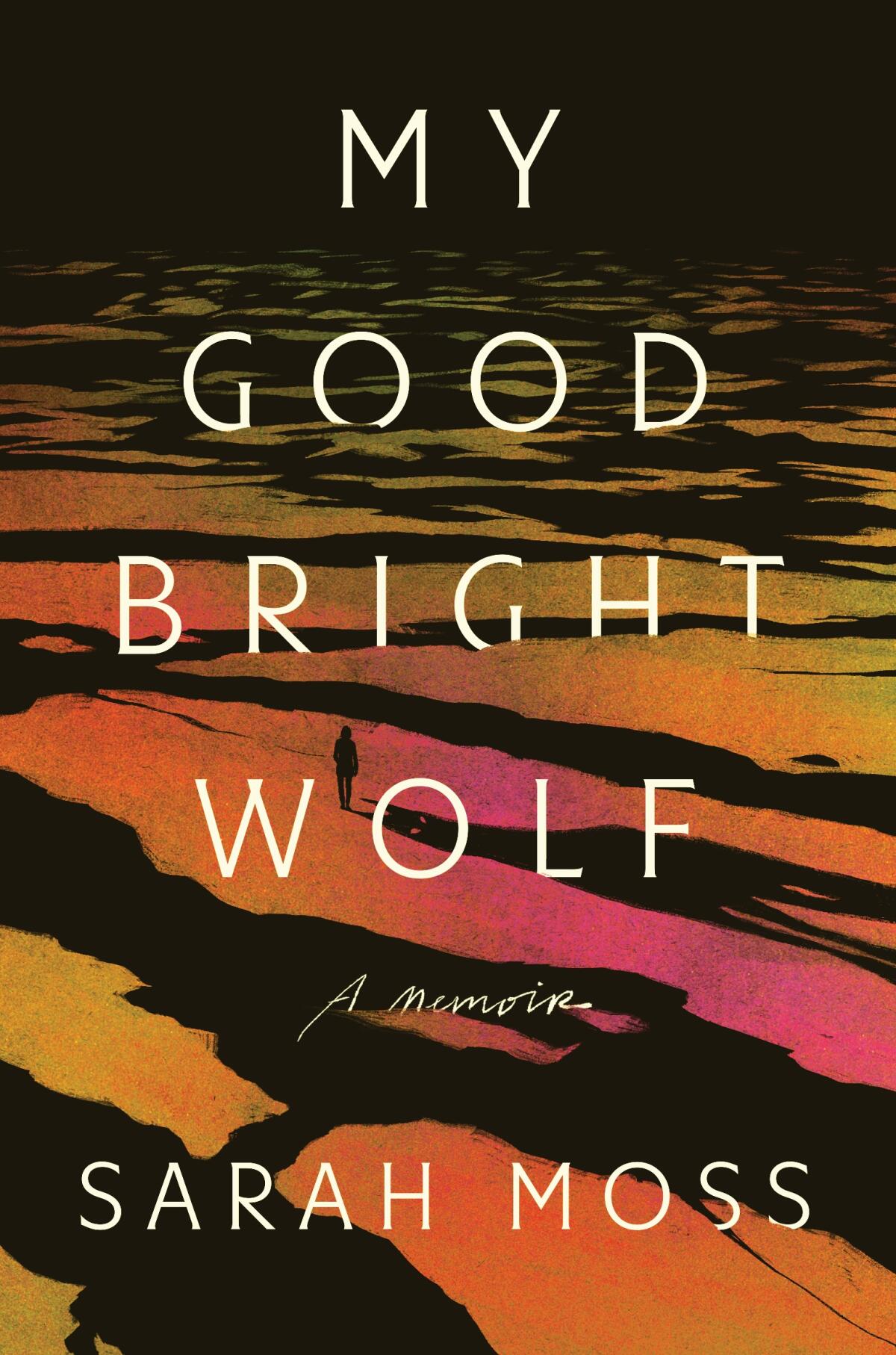

E-book Evaluation

My Good Vivid Wolf: A Memoir

By Sarah Moss

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 320 pages, $28

Should you buy books linked on our web site, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist impartial bookstores.

In two extraordinary memoirs, Sarah LaBrie and Sarah Moss chronicle the methods during which psychological sickness carves canyons and chasms in a life. For each ladies, the reward of writing got here with strings connected: the strands of DNA they carry from dad and mom who have been mentally unstable. For LaBrie, the fears of an inherited psychological sickness restricted her hovering creativeness. For Moss, a troublesome childhood manifested in life-threatening anorexia. For each, the lifetime of the thoughts supplied an escape.

LaBrie’s “No One Will get to Fall Aside” opens with a harrowing scene. “My grandmother in Houston calls me in Los Angeles to inform me my mom was just lately discovered on the aspect of the freeway, parked, honking her horn, her automobile stuffed with notes during which she outlined federal brokers’ plan to kill her.” It’s, the writer finds out, the final in a current collection of occasions during which her mom’s untreated schizophrenia has hit yet one more apogee.

For LaBrie, it’s a scary reminder of her childhood. Raised by her single mom, LaBrie acquired monetary assist and stability from her grandmother, an completed lawyer who was featured in a 1978 version of Ebony journal as an exemplar of how, as one Houston official mentioned, “For younger Blacks with abilities, that is the town of the twenty first Century.” At midlife, her grandmother gave up training regulation to open a mixture naturopathic drugs and ebook retailer. Her resilience in response to the historic legacy of racism and her sense that success is the results of focus and drive didn’t equip her to know her personal daughter’s psychological sickness.

LaBrie’s childhood is a mix of the advantages bestowed by her grandmother’s cash — which features a lovely home and a first-class schooling at an elite personal college — and residing with a mom whose schizophrenia has been labeled by household as a violent mood. In her household, she writes, “We cherished and needed one of the best for one another,” even when “it was coverage to let destiny take every particular person the place it might, even when doing so meant failing to avert catastrophe.” LaBrie turns into the doubled self who presents a shiny façade to the world to cover household chaos and denial.

A stellar scholar, LaBrie goes away to Rhode Island to attend Brown College. She is beset with melancholy and an consuming dysfunction, responses to the poisonous ranges of competitors amongst rich white kids who profit from the affirmative motion of legacy admissions and household entitlement. The racism of her Ivy League friends, couched in genteel politeness, corrodes the shiny self that she presents. LaBrie turns into associates with one other Black scholar, Sadie, and the 2 of them present one another with assist and companionship.

In her 20s, LaBrie’s life is structured by her pursuit of an MFA and her work on a novel that explores how the concepts of the vaunted thinker Walter Benjamin have an effect on the lives of her characters. She additionally enters a loving relationship with a younger filmmaker. Novel writing serves as a refuge from her mom’s deteriorating psychological state. Outdoors of the manuscript, unresolved emotions about her household trigger friction in her romantic and platonic relationships and burden her with the concern that she has inherited her mom’s sickness.

LaBrie brings a piercing astuteness and delicate voice to the dilemma raised by the author’s need to inform a narrative. Making an attempt to separate a household’s fictions from its realities is to enter locked closets stuffed with redacted recollections and erased tales which were overwritten to cover the reality. Psychological sickness, regardless of our elevated understanding of its causes and etiology, nonetheless causes disgrace. It may make an individual doubt herself, make her query whether or not her perceptions are proof of her personal diseased thoughts. For a author, the associated skill to imaginatively interpret actuality is turned inward.

In “My Vivid Good Wolf,” Sarah Moss’ household is deeply affected by rising up in Britain throughout a interval of social and political turbulence. Much more so, they’re affected by Britishness: In the UK, psychological sickness has been stigmatized by imperialist pretensions {that a} “stiff higher lip” distinguishes British character above different nations.

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

In some methods sidestepping this stigma, Moss refuses the jargon of psychology, eschewing phrases acquainted to People corresponding to melancholy, nervousness and trauma to focus as a substitute on the cultural and mental forces that outline who’s seen as regular and irregular inside society.

When she teases aside the structural underpinnings that prescribe gender, her analytical abilities are breathtaking. When she lets these buildings tumble and offers voice to the kid raised in a spartan emotional wasteland, she broke my coronary heart.

Moss’ mom, whom she calls “Jumbly Lady,” and her father, “the Owl,” have been inflexible of their worldviews, and people concepts have been used to manipulate their kids. They smash their clever, delicate daughter into fragments.

Moss seems again on that childhood and extends a deep empathy to her mom. She sees her as a part of “a technology generously educated proper to the doctorate by the welfare state after which walled up in marriage, baited and switched in spite of everything.” Her mom, like different second-wave feminists, raged in opposition to a system during which skilled aspirations and passions have been to be sacrificed so as to fulfill roles as dad and mom and wives. Moss grew up figuring out that she was “the entice” that stored Jumbly Lady at residence.

Moss’ mom used her mind to change into fanatical about home issues. She baked her personal bread, grew a backyard, rejected handy processed meals and made garments. Anger in opposition to her personal domesticity pushed Jumbly Lady to follow a wellness doctrine that made her really feel superior to the system she scorned. Household climbing and climbing journeys almost each weekend fed into her ethos of a main healthiness.

The Owl match the all-too-familiar mannequin of males who confirmed progressive views at work however have been misogynistic tyrants at residence. He was obsessed together with his spouse’s and daughter’s weights and wouldn’t permit sugar or butter in the home.

When Moss loses weight throughout an prolonged bout of sickness, as a substitute of noticing the flu’s ravaging results and expressing concern, her father praises her new slimness and makes use of it as a cudgel in opposition to his “fats” spouse. And he’s bodily violent.

Moss escaped into novels. She learn continuously, starting with Laura Ingalls Wilder and the British kids’s journey novels during which teams of children discover the countryside with little parental supervision — tales to inculcate values of self-reliance — and proceeded into the nineteenth century canon of writers that features Austen, the Brontёs and Tolstoy. Dwelling in an anxiety-producing residence, the place her dad and mom fought continuously about meals, she gives deep perception into the literary formation of a really perfect heroine — slim, self-controlled and white, one who rejects the corruptions of luxurious that deliver dissolution and debauchery.

From the confluences of tradition and household, Moss develops extreme anorexia. For her, refusing her dietary wants provides her management over her rising grownup physique. Girls’s our bodies are to be disciplined in the event that they need to be taken significantly in a male world. The consuming dysfunction adopted her into maturity and has had disastrous outcomes.

Like LaBrie, Moss goes again right into a darkish previous to deliver forth childhood recollections. Setting that childhood voice free comes at a value. A second voice, rendered in italics, continuously challenges her recollections, berating her for making up tales. She alternates that vulnerability along with her mature mind, which sees that the literature she learn to flee truly enforced British imperialism’s ethical values of racial superiority, sturdy bodily well being and modest womanhood.

Each LaBrie and Moss wrestle with the boundaries that rationalism imposes on emotional well being. LaBrie understands her mom’s analysis, however that understanding doesn’t reduce the ache of such data. Writing fiction requires an writer to harness voices in a single’s head that encourage characters and plots. How is that totally different from the free-rein voices that usually accompany schizophrenia?

For Moss, creativity and mind show to be insufficient instruments for controlling anorexia. “Understanding an issue shouldn’t be the identical as fixing it,” she writes. “The human capability for getting used to issues is usually a horrible energy.”

From these horrible strengths possessed by each LaBrie and Moss, horrible magnificence is born.

Lorraine Berry is a author and critic residing in Oregon.