There was extra flaying than I anticipated, although not essentially greater than I wished, at “Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Artwork of Tibet.” Any guests going to the Met’s exhibition in quest of tranquillity will discover a fifteenth-century flaying knife, a pair of flayed cadavers embroidered onto a rug, and one other flayed cadaver, with colourful guts stretched like warning tape round a palace. They could discover tranquillity, too—simply not the cuddly kind that American pop-Buddhism advertises. For the Himalayan monks of the early teen centuries, the perfect setting for initiation was a charnel floor, the place individuals left their lifeless to be eaten by wild animals. If faith can’t assist us amid the stink of rotting flesh, what good is it?

A millennium in the past, India was nonetheless a Buddhist headwater. Varied colleges flowed north and east, to China and Japan, however one, Vajrayana Buddhism, left its richest deposits on the Tibetan Plateau. It’s a pleasant irony of this present that remoteness can pace up transmission: the Himalayas had been uncrossable for 1 / 4 of the yr, however travellers wanted to get by means of all the identical, and lots of of them spent months close to the southern aspect of the mountains, ready out the snow and absorbing Buddhist tradition. By the thirteenth century, Vajrayana was near extinct in its personal birthplace, and Tibet, the ex-satellite, had grow to be the brand new heart. Ideologically, too, remoteness labored to the college’s benefit. Its leaders careworn Tantric chanting, ritualized intercourse, and different secretive practices, however, as Christian Luczanits suggests in an eloquent catalogue essay, they might be flashy about these secrets and techniques. A few of the most ravishing works right here had been painted in distemper on fabric, in order that they might be rolled up, transported anyplace, unfurled, and re-hidden the second they began to dazzle.

Tibetan Buddhism persuaded with sheer pictorial magnificence. Not solely with magnificence, in fact; impatient rulers appreciated that Vajrayana promised enlightenment in a single lifetime, versus the same old Buddhist dozens, and Kublai Khan unfold its teachings so far as his horsemen may experience. However, even right here, photos drove the faith’s growth and begat different photos. Kings commissioned mandalas to clinch future success; after they gained the battle or survived the plague, they celebrated by demanding extra opulent variations. You will discover Tugh Temür, Kublai Khan’s great-great-grandson, within the backside left nook of a fourteenth-century silk mandala he requested. Child Khan is nowhere close to crucial of the various beings depicted right here, however it’s an honor simply to be included. Facilities and satellites are nonetheless the thought; above him float a number of squares inside circles, and because the geometric shapes get smaller and extra central the figures inside get extra vital—not mortals however minor deities, not minor deities however the massive man, Vajrabhairava. Know him by his blue pores and skin and buffalo head.

Sound complicated? It’s, however one factor this mandala definitively isn’t is cumbersome. The shapes appear to slip soundlessly in opposition to each other; the in-between areas are loosened up with beautiful floral squirms of inexperienced thread. Even after I squint on the little copy within the catalogue, I get a way of a complexity that has been captured with out being tamed—too massive to belong to any single individual, least of all of the one who paid for it.

If I had been smarter, or stupider, I’d attempt to use the remainder of this assessment to settle the query of what Tibetan mandalas (not the one artwork works right here, however essentially the most putting) had been used for. I can take some consolation in the truth that not even the Met’s specialists agree on an actual reply. At a current convention hosted by the museum, an eminent professor claimed that they might be understood primarily as meditation aids; within the catalogue, one other insists that “there isn’t a foundation for this interpretation.” There may be loads of foundation for the interpretation that mandalas are symbols of the divine cosmos, designed to show initiates about the true factor, except mandalas are vessels wherein the divine resides, nothing symbolic about them. They’re lecturers and icons, maps and billboards, propaganda for the Buddhists who create them and likewise for the kings who fund them. Probably the most well-known ones don’t even exist, since they’re studiously destroyed as quickly because the monks end making them from sand.

“Portrait of a Kadam Grasp with Buddhas and His Lineage” (c. 1180-1220).Artwork work courtesy Michael J. and Beata McCormick Assortment

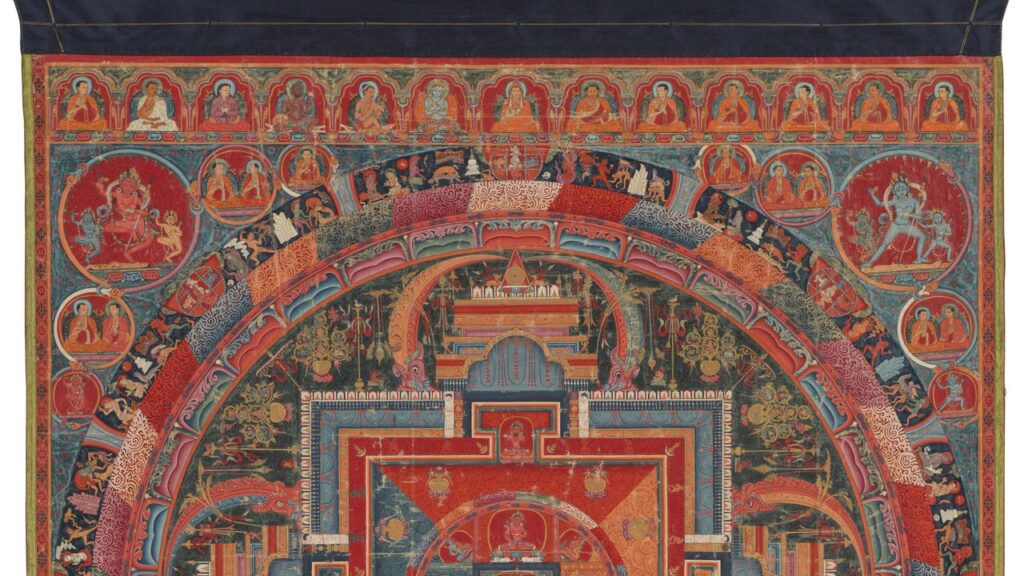

Mandala-gazing requires a buffet of prepositions, an “at” that can be an “in” that can be a “down upon.” You’re meant to start out alongside the perimeters and proceed clockwise, passing the images of monks, deities, or patrons of their neat squares. From there, go inward, to a round plate on which a four-gated palace rests. Usually, every gate is guarded with a pair of prongs that counsel a vajra, a Buddhist scepter; make it previous these and also you’ve damaged into the house of the principle deity, who sits on the heart, circled by lesser deities whereas waving a weapon or, relying on the model, embracing a consort. You’ll be able to think about every layer stacked on high of the earlier one (three-dimensional mandala fashions are organized this fashion), in order that the farther in you progress the upper the picture pokes out of the image aircraft. Inward turns into upward.

Both approach, you’re doing together with your eyes what Buddhism says you are able to do together with your life: continuing from outer to inside, base to noble, ignorant to enlightened. The crawl from one to the opposite issues as a lot because the enlightenment itself—skipping the charnel grounds isn’t an possibility. Observe no fewer than eight of them on the outskirts of a single eleventh-century Nepalese mandala. Greenish jackals feast whereas birds nibble on skulls, and why shouldn’t they? They’re a part of the cosmos, too. The purple surrounding this mandala’s central deity is a Buddhist image of purity, but in addition a reminder that purity begins with the flesh and blood that everyone will get without cost.

Even when nothing about Buddhism, even in case you’re in no temper to be taught, this present could be value visiting for the eerie loveliness of the colour. One mandala, depicting the goddess Jnanadakini, has barely a crack to point out for nearly seven hundred years of current. The colours are all pomp and sizzling splendor: purple grabs maintain of softer pinks and jades and apricots and makes them burn. Slower to strike, however no much less sensational, are the summary patterns of frantic, curling traces you discover all through, as if Himalayan artists of the late fourteenth century had in some way visualized mind coral. When line and shade work collectively at full tilt, as they do behind the partitions of Jnanadakini’s palace, the patterns get so dense that they might nearly be strong fills. Peace is made to really feel like a state of faint, cheerful vibration. “Biography of a Thought,” an enormous mandala portray that the up to date Nepalese artist Tenzing Rigdol contributed to the present’s atrium, is pat by comparability—blue is simply blue, strong is simply strong, and taking this all in after marvelling at the true factor is like washing nice wine down with syrup.

Distemper doesn’t survive seven centuries except somebody is guarding it from breath and daylight. One level on which all of the Met’s specialists agree is that mandalas weren’t made for mass gawking: most Vajrayana initiates journeyed by means of them with an skilled grasp as a information. That was in all probability a shrewd transfer on the grasp’s half. Photos—the nice ones, at the very least—are at all times richer than their official meanings, which is why so many religions police or ban them. In a distemper-on-cotton mandala from 1800 or so, the deity Ekajata resides in a palace guarded by corpses and surrounded by smoky darkness. There’s an apparent development right here, from smoke to physique and physique to divinity, however perhaps it leads from divinity all the way in which again to smoke, which will get brighter and livelier the longer we stare. Thick clouds appear to push out past the rectangle they’re in, and past any bounds anybody may attempt to place round them. Spiritual artwork may have been doing a lot extra with smoke this complete time, I assumed as I appeared. Fireplace and water have hogged the highlight for too lengthy; smoke has its personal glamour, its personal deathless wriggle. On this mandala, whether or not the monks authorized or not, it will get the starring position it was born to play. ♦