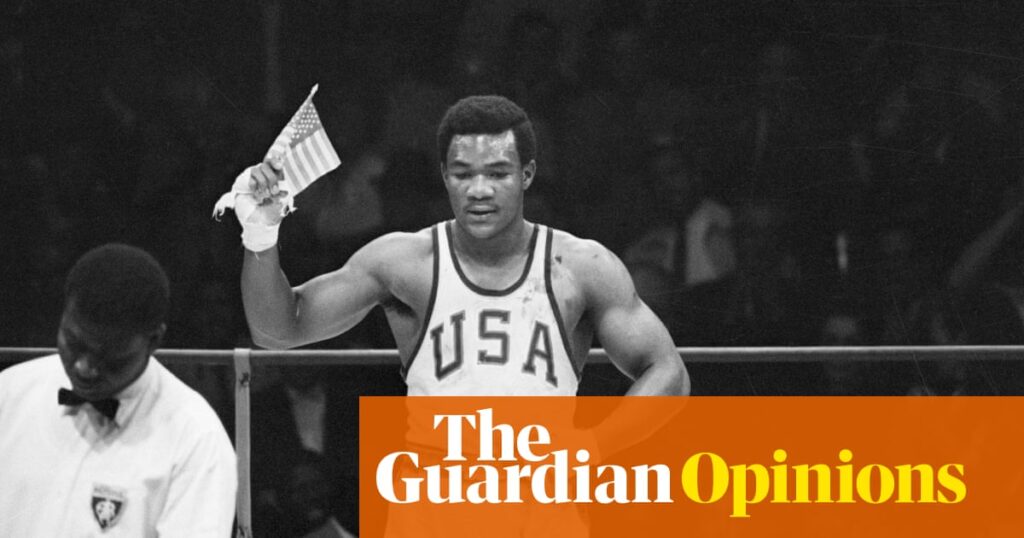

When a teen from Texas named George Foreman waved a tiny American flag within the boxing ring after winning Olympic gold in 1968, he had little consciousness of the political minefield beneath his measurement 15 toes. The second, captured by tv cameras for an viewers of hundreds of thousands throughout one of many most volatile periods in American history, was immediately contrasted with one other picture from two days earlier on the similar Mexico Metropolis Video games: Tommie Smith and John Carlos, heads bowed and black-gloved fists raised in salute through the US nationwide anthem, a silent act of protest that might develop into one of many defining visuals of the twentieth century. Their message was unmistakable: a rebuke of the nation that had despatched them to compete whereas persevering with to disclaim civil rights to individuals who appeared like them. Their motion was seen as defiant resistance, Foreman’s as deference to the very methods of oppression they had been protesting.

Foreman’s flag-waving, unremarkable in virtually some other context, grew to become a lightning rod. For a lot of, particularly these aligned with the rising tide of Black Energy, the gesture felt tone-deaf at greatest, an outright betrayal at worst. How might a younger Black man, representing a rustic nonetheless brutalizing his personal individuals, rejoice it so enthusiastically? However that studying, whereas emotionally comprehensible amid the fevered upheaval of 1968, misses one thing deeper – about Foreman, about patriotism, and in regards to the burden of symbolic politics laid on the shoulders of Black athletes.

To grasp the backlash the 19-year-old Foreman confronted within the context of 1968, significantly from throughout the Black group, is to grasp the temper of that 12 months: a procession of funerals and fires, of uprisings in Detroit and Newark, of younger individuals buying and selling desires of integration for the sharp rhetoric of militant self-determination. Dr Martin Luther King Jr had been gunned down in Memphis simply months earlier. Black Energy was now not a whisper in again rooms or faculty school rooms – it had develop into a rallying cry, a method, a stance. And in that charged environment, there appeared to be just one acceptable technique to be Black and politically aware: with fist raised, backbone straight, voice sharpened by injustice.

In that local weather, Smith and Carlos’s silent, defiant protest was seismic. They paid dearly for it – expelled from the Video games, vilified at house and exiled from skilled alternative for years. They had been heroes, then and now. However the demand for unity behind that exact sort of protest was robust. To many, in that second, there was just one acceptable technique to be Black and political. Foreman’s flag violated that code. It didn’t converse the language of protest. It didn’t identify the enemy. And so, some noticed it as a profound misstep.

Foreman had lengthy insisted that there was no assertion embedded within the flag he waved. “I didn’t know something about [the protest] till I acquired again to the Olympic Village,” he stated years later. “I didn’t wave the flag to make an announcement. I waved it as a result of I used to be completely satisfied.” However in 1968, happiness was a political act, and its symbols didn’t float innocently above the fray. To wave the American flag in that second – as tanks rolled by means of Chicago, as King’s assassination nonetheless echoed within the nationwide conscience – was to wade, nevertheless unknowingly, right into a pool already churning with stress and that means.

That sort of apolitical happiness wasn’t simply suspicious – it was infuriating to these risking all the pieces to problem the systemic racism on the basis of American society. The truth that the mainstream white media embraced Foreman as a “good” Black athlete in distinction to Smith and Carlos solely deepened the rift. He was positioned, maybe unintentionally, because the secure image of patriotism, the counter-image to fists within the air.

And but Foreman’s story was by no means easy. He grew up poor in Houston’s Fifth Ward, a tricky and segregated neighborhood. He discovered boxing by means of the Job Corps, a federal anti-poverty program. For Foreman, the flag didn’t symbolize a authorities that had failed him – it represented a rustic that had provided him a means out. His patriotism was something however performative; it was deeply private.

Too typically, completely different experiences of Blackness are mistaken for ideological betrayal. Not each expression of pleasure in America is a denial of its sins. Generally it’s a hard-earned survival mechanism. For Foreman, the flag might have symbolized escape, alternative and the dream that one way or the other, regardless of all of it, he belonged.

Nonetheless, the criticism adopted him, cussed and sharp. He was branded an Uncle Tom, accused of pandering to white America, made to really feel, by his personal account, unwelcome in lots of Black areas. His response was to not clarify however to retreat. Within the ring, he grew to become a fearsome presence – indignant, sullen and distant. Exterior it, he stated little, and appeared to hold a quiet fury beneath the floor. When he lay waste to Joe Frazier in 1973, knocking him down six occasions in two rounds to say the heavyweight crown, he celebrated not with a smile however with a sort of grim inevitability. He appeared much less like a champion than an avenger.

However narratives have a means of bending, particularly in American life, and Foreman’s finally did. Not lengthy after shedding all of it with his crushing loss to Muhammad Ali in Zaire the next 12 months – a defeat that humbled and haunted him – he disappeared for a decade. He discovered God, grew to become a preacher, opened a youth middle. When he returned to boxing within the late Eighties, older, heavier and unfashionably mild, the general public met him with one thing approaching affection. He smiled now. He cracked jokes. He appeared on speak reveals. And when, at 45 years outdated, he reclaimed the heavyweight title in one of many sport’s most inconceivable comebacks, it felt not like redemption however reinvention.

The identical man who as soon as waved the flag and was scorned for it now hawked hundreds of thousands of countertop grills bearing his identify. He starred in a prime-time network TV sitcom. He named all 5 of his sons George. He leaned into the parable and made it charming. In doing so, he reshaped the cultural that means of his picture – from the quiet bruiser to the joyful elder statesman, an emblem of resilience, reinvention and a sort of pragmatic hope. There’s a reputable argument that he succeeded Invoice Cosby as America’s dad.

We must always not neglect, nor flatten, the unconventional readability of Smith and Carlos’s gesture. Nor ought to we mistake Foreman’s act for something it was not. However maybe we will now make room for each. Black patriotism has by no means been a monolith; it has at all times contained stress, ambiguity, contradiction. Some categorical it by means of protest, others by means of perseverance. A fist raised, a flag waved – each may be acts of affection, not of submission, however of insistence: that the nation be made to reside as much as its promise. And in a nation that usually calls for that Black individuals carry out both rage or gratitude, George Foreman dared to be one thing else: complicated.

The enduring lesson of 1968 is just not that one type of Black political expression is inherently extra legitimate than one other, however that the burden positioned on Black athletes to represent a collective expertise is commonly impossibly heavy. Each gesture is scrutinized. Each silence is interpreted. Each celebration is suspect. In that sense, Foreman’s flag was by no means nearly pleasure – it was in regards to the impossibility of being apolitical in a physique already politicized by historical past. He didn’t salute an ideal America. He saluted the opportunity of one.