Southern Queer Model (1985–1995): Images, Performativity & Spirituality within the HIV/AIDS Archive

“I need to see the blessed face

Of Him who died for me

Sacrificed his life for my liberty”

— Yolanda Adams, My Liberty (1993)

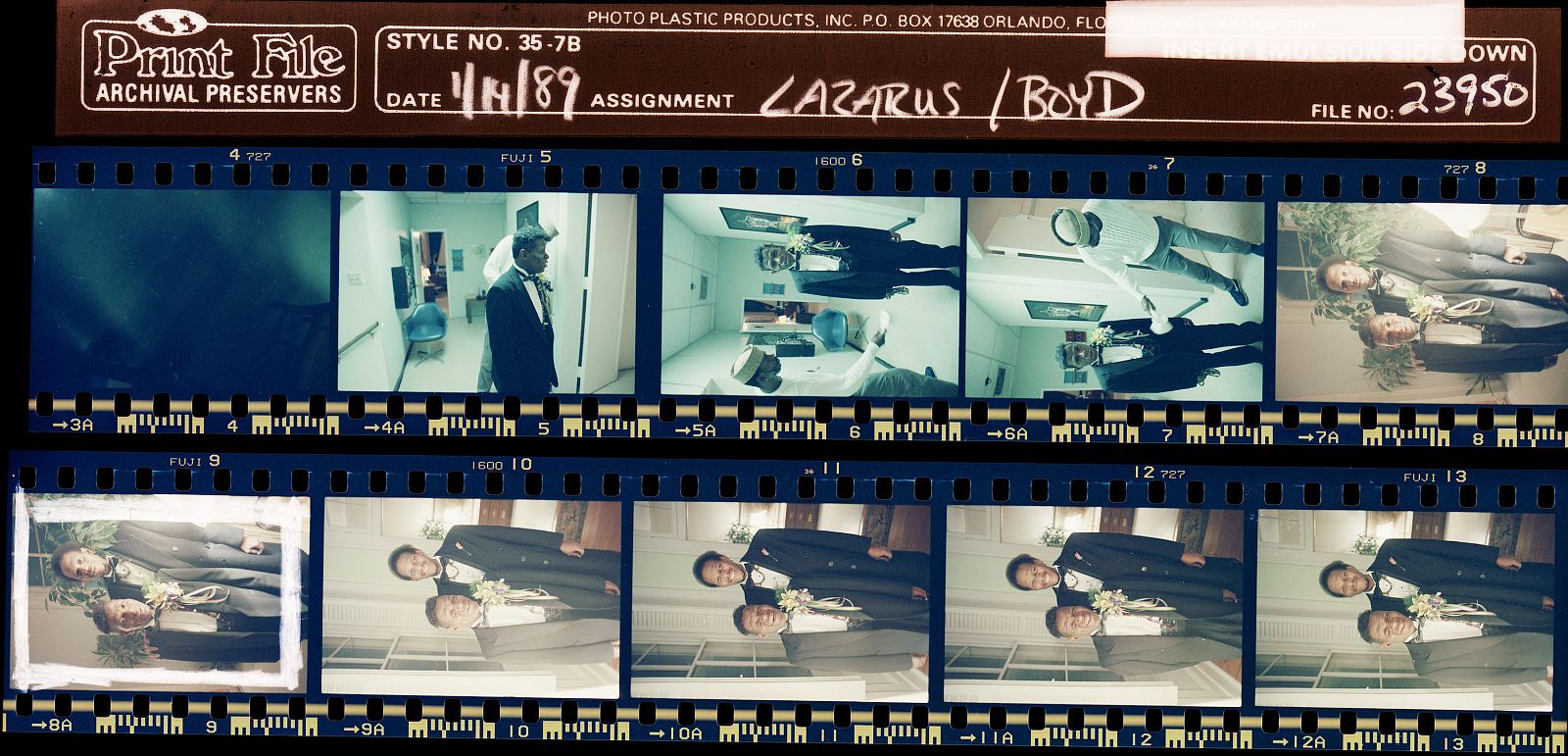

In a roll of two strips of 35 mm movie, a sequence of portraits reveals two Black homosexual males wearing black fits, white shirts, and bow ties. On the lapels of their jackets, they put on boutonnières—small floral ornaments sometimes worn on formal events similar to weddings, balls, or celebratory church ceremonies. The person on the proper wears a single pink flower, whereas the boutonnière worn by the person on the left is extra elaborate and indulgent. Each males put on cummerbunds—broad, often pleated waistbands typical of tuxedos—and Mardi Gras necklaces. Their pose suggests an in depth relationship, presumably as a pair. In one of many photographs, a Ficus plant seems within the background, its lush leaves framed by home windows and family objects similar to lamps, furnishings, framed photos, and carpets, providing the viewer a way of residence and interiority. The {photograph} was captured in 1989 by Andrew Boyd at Challenge Lazarus, a residential therapy heart in New Orleans based in 1985 for people residing with HIV/AIDS and missing secure housing.(1)

G. Andrew Boyd, Untitled (couple in fits at Challenge Lazarus, in a residential therapy heart for people residing with HIV/AIDS in New Orleans), 1989. The Historic New Orleans Assortment

Within the phrases of bell hooks, “Cameras gave to Black of us, irrespective of sophistication, a method by which we might take part absolutely within the manufacturing of photographs. Therefore it’s important that any theoretical dialogue of the connection of Black life to the visible, to artwork making, make pictures central. Entry and mass attraction have traditionally made pictures a strong location for the development of an oppositional Black aesthetic.”(2) Alongside these traces, one other picture by Boyd reveals a person utilizing a brush to take away lint from the couple’s black tuxedos. This gesture, a part of the wardrobe and photographic manufacturing, means that the lads wore formal apparel particularly for the portrait and should have commissioned the {photograph} to commemorate the second.

Element, G. Andrew Boyd, Untitled (couple in fits at Challenge Lazarus, in a residential therapy heart for people residing with HIV/AIDS in New Orleans), 1989. The Historic New Orleans Assortment

The connection between pictures, reminiscence, and cultural survival is additional elaborated by artwork historian Krista Thompson, who notes that “The photographic medium, which regularly captures an unrecoverable second from the previous, permitting it to reside ‘freeze-framed’ in different instances and areas, might need a particular analogous relation to African diasporic communities who are sometimes minimize off or faraway from areas and instances.”(3) Constructing on Thompson’s view of pictures’s significance for African diasporic topics—incessantly displaced or traditionally excluded—the portraits made at Challenge Lazarus problem dominant visible narratives of HIV/AIDS.(4) Somewhat than depicting people on the brink of dying, these photographs supply various representations of intimacy, type, care, and survival.

On this ongoing analysis, I current a choice of pictures that doc the lives of Black, Brown, and Latinx queer males—distinct but overlapping communities that are marked by shared experiences of marginalization—throughout the HIV/AIDS disaster within the Southern United States.(5) These photographs seize the intersection of queerness, spirituality, type, and representations of racialized topics, shedding mild on the epidemic’s profound affect on Southern LGBTQ+ communities. The challenge focuses on the interval from 1985 to 1995, and is marked by vital social, political, and medical developments associated to HIV/AIDS. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan publicly acknowledged AIDS as a public well being downside for the primary time, having beforehand prevented referencing it, and his administration confronted criticism for inadequately funding analysis. Authorized rules emerged to shut venues related to “high-risk sexual exercise,” similar to bathhouses, whereas organizations like ACT UP advocated for entry to remedies and medical trials. Medical advances—together with the approval of AZT in 1987 and the primary protease inhibitor in 1995—paved the way in which for extremely energetic antiretroviral remedy (HAART).(6) By the early Nineties, AIDS had grow to be the main reason behind dying for Individuals aged 25 to 44, underscoring the urgency of those developments. This curatorial challenge captures the complexity and transitions of this tumultuous decade, providing a visible narrative of endurance, activism, and pleasure within the American South.

In comparison with cities like New York and San Francisco, the Southern United States confronted distinctive challenges in addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic throughout the Eighties and Nineties. Regardless of an infection charges corresponding to the hardest-hit city areas, restricted healthcare entry, entrenched stigmas round sexuality, and reluctance to deal with sexual well being and LGBT rights sophisticated responses.(7) As scholar Celeste Watkins-Hayes notes, “HIV/AIDS is an epidemic of intersectional inequality fueled by racial, gender, class, and sexual inequities on the macro-structural, meso-institutional, and micro-interpersonal ranges.”(8) These structural inequities disproportionately affected African American and Latinx communities, shaping each publicity to the virus and the social, medical, and political responses to the epidemic.

Intersecting forces of racism, Christian fundamentalism, classism, and right-wing politics form LGBTQ+ experiences within the Southern United States. The area encompasses huge socioeconomic and ecological variations, from the plantation landscapes of the Deep South to the poverty-stricken valleys of Appalachia, and from the isolation of the Ozarks to the Gulf Coast’s “Redneck Riviera.”(9) In keeping with Mexican artist and activist Leo Herrera, Southern queers have lengthy developed methods to climate each literal and political storms, demonstrating not merely resilience however resplendence.(10) These methods have discovered expression in city facilities like New Orleans, Dallas, Miami, Houston, and Atlanta, all of which served as early facilities of LGBTQ+ activism. Nonetheless, exploring Southern queer historical past stays difficult, because of the restricted availability of archives and shortage of data.(11)

Historian James T. Sears captures this rigidity, observing that “Southern historical past is rarely easy and rarely straight,” reflecting the complicated interaction of regional contexts and queer reminiscence.(12) Students like E. Patrick Johnson additionally emphasize how gender, class, and race intersect to form the South’s queer range. In the course of the Nineteen Seventies and early Eighties, these divisions fragmented LGBT communities, and lots of homosexual males didn’t brazenly focus on HIV till the early Nineties, typically struggling to grasp the sudden pneumonia-related deaths of mates starting in 1981.(13) In rural areas, insufficient medical companies and prevention had been deepened by cycles of poverty and insecurity, additional compounding the disaster and making the South one of the difficult areas for LGBTQ+ residents.