(This submit initially appeared as a visitor submit on Linda Bennett Pennell’s weblog, History Imagined.)

In researching my historic novels set in nineteenth-century America, I’ve come throughout plenty of folks, now obscure, who should be remembered for his or her heroism. One is David Ruggles, a black abolitionist.

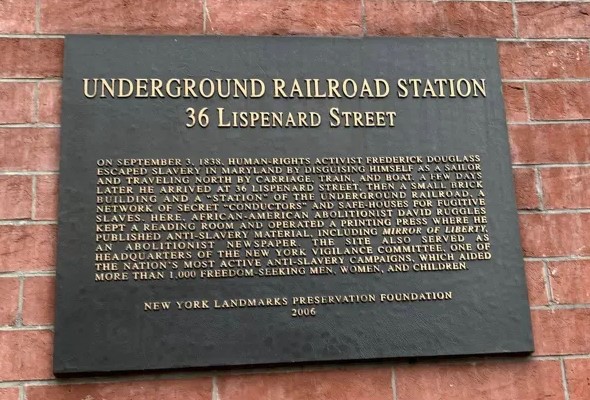

Born in Lyme, Connecticut, on March 15, 1810, Ruggles, the son of a blacksmith, took to the ocean at age fifteen and ended up in New York Metropolis, the place he grew to become energetic within the abolitionist motion and ran a grocery retailer for a time period. In 1834, he moved to Lispenard Road in decrease Manhattan and opened a bookstore and circulating library specializing in abolitionist literature. Quickly he started publishing his personal pamphlets—a daring transfer in a metropolis that was not notably pleasant to the anti-slavery motion. His retailer was set on fireplace in 1835. Unintimidated, Ruggles helped type the New York Committee of Vigilance, which helped escaped slaves and fought towards the kidnapping of each free blacks and escapees. His home would quickly grow to be a cease on the Underground Railroad.

In 1838, Frederick Bailey, a fugitive from slavery, was directed to Ruggles’ home and spent a minimum of per week there. Whereas there, Bailey summoned his fiancée from Baltimore to New York, and the couple married in Ruggles’ home. (Ruggles himself was a lifelong bachelor.) On Ruggles’ recommendation, Bailey modified his surname to Johnson, however quickly would change it once more, changing into often called Frederick Douglass. Douglass was certainly one of a whole bunch whom Bailey helped to freedom.

Sadly, Ruggles’ eyesight started to deteriorate when he was nonetheless a younger man, making it untenable for him to proceed his publishing actions, which included a journal, the Mirror of Liberty. Mates invited him to remain on the Northampton Affiliation of Schooling and Business, a cooperative neighborhood simply outdoors of Northampton, Massachusetts. He arrived there in 1842, however his normal well being was failing as properly. Ruggles lastly tried hydrotherapy, often called the “water remedy,” below the supervision of Dr. Robert Wesselhoeft, who operated a well-liked water-cure in Brattleboro, Vermont, however suggested Ruggles by letter. As Ruggles’ biographer, Graham Russell Gao Hodges, factors out, Dr. Wesselhoeft was apparently unwilling to threat the social outrage that may consequence from having Ruggles bathing facet by facet with white purchasers.

Regardless of the therapies, Ruggles’ well being and eyesight improved solely marginally, however he was happy sufficient with the outcomes to start treating sufferers himself. Amongst his sufferers was a reluctant Sojourner Fact, who grumbled, “I shall die if I proceed in it, and I’ll as properly die out of the water as in it.” After ten weeks, nevertheless, she admitted that she “had by no means loved higher well being in her life.”

Ruggles quickly opened his personal water-cure institution within the Northampton space. One other of his sufferers was abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who stayed there in the course of the summer time of 1848. Writing to Maria W. Chapman on July 19, 1848, Garrison said: “The expertise of the primary day runs thus: — a half tub (which I ought to contemplate a complete one and 1 / 4) at 5 o’ clock, A.M.; rubbed down with a moist sheet thrown over the physique at 11 o’clock; a sitz tub at 4, P.M.; a foot-bath at half previous 8, P.M.; and at 5 this morning, a shallow tub which is to be adopted at 11 by a sprig baptism.” In a letter to his spouse on July 23, 1848, Garrison bragged that he had withstood the trials of being “packed in a moist sheet, or drenched from head to foot, or immersed throughout” and had not “uttered a groan, or heaved a sigh, or shed a tear, or faltered for a second.” He famous that there have been 19 sufferers, principally males, and added, “There doesn’t appear to be any pro-slavery among the many sufferers; if there actually is, it has not been manifested by any phrase or signal, and I hope it will likely be washed out of them.” Upon his discharge, Garrison proclaimed, “My aversion to chilly water has been pretty conquered. I’m now its earnest advocate.” Different sufferers of Ruggles included Mary Brown, whose husband John would later be hanged for main the raid on Harpers Ferry. Mary, who had had plenty of youngsters and had been ailing for a while, advised her son-in-law that she believed that the water remedy could be “her solely salvation.” Later, she would use the water-cure to deal with her family’s illnesses.

Sadly, Ruggles couldn’t remedy himself. Though he ran his water remedy nearly till the tip, he died on December 16, 1849. He was not but forty. Ruggles was buried in his household plot in Norwich, Connecticut. Many would pay tribute to this man who had led a brief, however full and heroic life. Frederick Douglass later recalled him as that “whole-souled man, absolutely imbued with a love of his and hunted folks.”

Sources:

Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855).

Graham Russell Gao Hodges, David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York Metropolis (Chapel Hill, NC: College of North Carolina Press, 2010).

The Liberator, July 27, 1849 (commercial)

Walter M. Merrill, ed., No Union With Slave-Holders: The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, 1841-1849 (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard College Press, 1973).

Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz, The Tie That Sure Us: The Ladies of John Brown’s Household and The Legacy of Radical Abolitionism (Ithaca and London: Cornell College Press, 2013).

Joel Shew, The Hydropathic Household Doctor (New York: Fowler and Wells, 1854).

Margaret Washington, Sojourner Fact’s America (Urbana and Chicago: College of Illinois Press, 2009).