I am standing outdoors the hallowed partitions of the Market theatre, Newtown, Johannesburg. That is the place the place Athol Fugard – absolutely the best of South African playwrights and one in every of my all-time theatre heroes – staged performs together with Hi there and Goodbye and The Island. The latter was co-written with fellow theatre greats, actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona. Now it’s the flip of a little-known English author and his play Breakfast With Mugabe. That is, as they are saying, one of many days of my life.

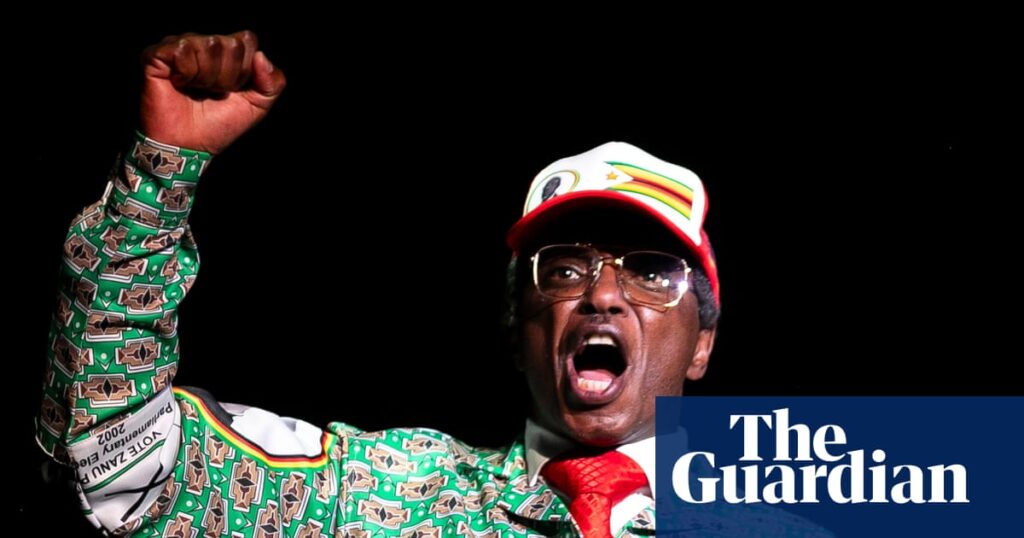

In 2001 my script felt like pressing work. Elections loomed in Zimbabwe, and Robert Mugabe was reportedly unleashing horrible violence in his bid to cling to energy. To many within the UK “President Bob” had lengthy been a monster. However what, I puzzled, created the monster?

The play finds Mugabe holed-up in State Home, pursued by the bitter spirit of a long-dead comrade. Denied assist by conventional healers, the previous liberation chief reluctantly turns to a white psychiatrist. Cue the unravelling of historical past.

Curiosity in Breakfast With Mugabe was quick, and protracted. The late (and far missed) Antony Sher directed a Royal Shakespeare Firm manufacturing that travelled from Stratford in 2005 through Soho theatre to the West Finish in 2006. An audio model flourished on BBC Radio 3 and the World Service; a second UK manufacturing adopted, whereas within the US a manufacturing by Two Planks & A Ardour (directed by David Shookhoff) clocked up 100 performances on New York’s forty second Road. One other manufacturing was staged in Berkeley.

Since then, Mugabe has died and Zimbabwe bumps alongside in comparative peace. So a brand new manufacturing – particularly in South Africa – got here as a shock.

Based on Greg Homann, the thought blossomed slowly. In 2022, Greg – whose theatre work spans the US, UK and South Africa – was affiliate artist on the Midlands Arts Centre in Birmingham. Then his “dream job” grew to become a actuality. Returning to South Africa as creative director of the Market theatre, one of many first artists he encountered was a younger director quick constructing a popularity as an progressive theatre-maker. Calvin Ratladi had, someday in 2016, came upon a duplicate of Breakfast With Mugabe. The play caught with him; would the Market produce it?

Sadly, that plan stalled. Then, earlier this yr, Ratladi was named Customary Financial institution’s younger artist of the yr for theatre. This award is kind of a gong (its first winner was Richard E Grant). It brings with it assist for a inventive undertaking – and a possibility was glimpsed. If Ratladi nonetheless held a torch for his Mugabe undertaking, the Market theatre would host. Remarkably, he was as eager as ever. A theatre polymath and famend incapacity activist, for him this four-handed, pressure-cooker play of psychology and spirituality introduced thrilling new challenges.

If this partly solutions the “why right here, why now?” query, why do Ratladi and Homann suppose the play resonates within the new South Africa?

For Homann, the play typifies the Market’s longstanding dedication to “an entwining of politics and theatre” – a practice important to the theatre’s co-founders Barney Simon and Mannie Manim, and to one of many many playwrights they championed, Athol Fugard, who sadly died in March. Latest reveals on the Market have examined the life and legacy of different important South African figures, amongst them Winnie Mandela and Robert Sobukwe. As Ratladi factors out, Breakfast With Mugabe extends this custom; a play a few hero of the liberation motion – this time from outdoors South Africa, and one whose legacy is hotly contested.

That is very true amongst Zimbabweans, an estimated one to a few million of whom now stay in South Africa. Hearings into the Gukurahundi in Matabeleland within the mid Nineteen Eighties have solely simply begun in earnest. In that bloodbath, Mugabe ordered his military’s North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade to suppress his occasion’s opponents. An estimated 20,000 Zimbabweans have been murdered.

On the manufacturing’s first night time in Johannesburg, it was clear the play retains its chew. Themba Ndaba and Craig Jackson lock the president and his shrink in a horrible wrestle for supremacy; Gontse Ntshegang shines because the manipulative Grace Mugabe, drawing howls of laughter for her indiscretions as “the First Shopper”, whereas Zimbabwean-born Farai Chigudu exudes menace – and barely managed violence – because the bodyguard/secret policeman, Gabriel.

With the primary three performances bought out, audiences (as audiences will in South Africa) whooped, gasped and sighed at each zinger or put-down – verbal or bodily – delivered by the solid.

I’ve been fortunate. The play has virtually at all times been nicely acquired by audiences in addition to critics. Within the US nonetheless, what I believed was a play about colonial culpability was celebrated as an essay on interracial battle, pure and easy. Do Individuals wrestle to see their nation implicated as a colonial energy?

In South Africa in contrast, it’s the influence of colonial oppression that deafens. Publish-liberation rewards – the justice so lengthy awaited by black South Africans – by no means materialised for a lot of. How the nation’s present authorities can ever ship redress is a hot-button political concern for President Cyril Ramaphosa – and one essential to the way forward for South Africa’s 63 million inhabitants.

And what does Ratladi’s surprising, bracing new manufacturing provide the playwright? A lesson. No matter we might suppose we’ve written, a play can – just by shifting its context in time and house – make us suppose and really feel one thing new. It’s in any case play – a residing, unfolding, mutable factor. Like all true play, its punches don’t at all times land the place anticipated.