Bestselling horror writer Ania Ahlborn has lengthy been identified for crafting deeply unsettling tales that linger lengthy after the ultimate web page.

From her breakout novel Brother to the chilling Seed and The Shuddering, Ahlborn’s work explores the darker corners of human emotion with cinematic aptitude and psychological depth.

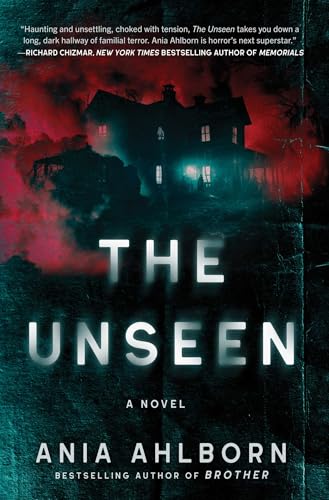

Her newest novel, The Unseen—out August nineteenth—could also be her most haunting but. Set in a distant Colorado farmhouse, the story follows Isla and Luke Hansen, a pair grappling with devastating loss, whose already fragile household begins to fracture when a mysterious, nonverbal youngster seems on their property.

As Isla turns into more and more obsessive about the boy, unusual and reality-bending occasions escalate, plunging the household right into a nightmare that blurs the road between grief and horror.

We caught up with Ania Ahlborn to debate the inspiration behind The Unseen, the emotional weight of writing about loss, and why creepy children by no means get previous.

Janelle Janson: What was the spark or preliminary concept that impressed The Unseen? Did Rowan’s character come first, or the theme of grief?

Ania Ahlborn: It began with grief. I imply, truthfully, what does not? I didn’t got down to write a fundamental creepy-kid-comes-out-of-the-woods story. The Unseen is about ache that ruins your reminiscence, your sleep, your physique. The sort that exhibits up out of nowhere and pretends to be your child.

Rowan was the primary character I knew—the one which formed your complete story—however he got here after the theme. He’s a metaphor, an echo of the kids Isla has misplaced. However he’s a mistaken type of grief, like if sorrow grew legs and referred to as you Mommy.

JJ: Rowan is without doubt one of the most unsettling youngsters in current horror. What influenced his creation? Any real-life inspirations, legends, or archetypes?

AA: He’s not based mostly on anyone legend, although I’ve at all times been fascinated by changeling folklore and real-life tales of feral youngsters. Each have that very same uncanny almost-ness. Rowan faucets into that. He’s not evil. He’s simply… not appropriate in the best way we, as a society, outline “regular.”

And I don’t know should you’ve ever had a child stare at you silently for 5 complete minutes with out blinking, however it’s a horror film. Youngsters may be sleep-deprived goblins with no quantity management and really questionable motives.

Rowan is simply that—distilled and sharpened into one thing that’ll make your pores and skin crawl.

JJ: The isolation within the story is palpable, regardless of there being seven members of the family. Was that distinction intentional?

AA: Completely. I feel a number of the loneliest moments in life occur whenever you’re surrounded by people who find themselves supposed to know you and do not. The Hansens are all coping with the identical loss, however they’re every dealing with it in another way.

And the truth that Isla is not attempting to tug the household collectively, and as an alternative lets her grief bury her, is the true coronary heart of the story.

She may have pivoted in the other way. However she doesn’t. She appears at her life and sees not one thing good, however one thing missing. And that perspective finally ends up being the household’s undoing.

JJ: Isla is a sophisticated, usually unlikable character. What was your strategy to writing her obsession and descent?

AA: I by no means meant to make Isla likable. I wished her to really feel actual, as a result of grief isn’t well mannered. It’s not swish or sympathetic. Generally it curdles into obsession, and typically that obsession wears a mom’s face and tucks the youngsters into mattress.

Isla’s descent isn’t sudden—it’s sluggish and quiet, the best way most real-life unravelings are. She doesn’t get up in the future and lose it. She simply stops resisting. Little by little, she palms herself over to the model of actuality that hurts much less, till that actuality doesn’t look very similar to the reality anymore.

I’ve heard readers complain that a whole lot of my characters aren’t likable, however I’m undecided these specific readers are true horror connoisseurs. Likable characters are exhausting to search out on this style, particularly in the event that they mirror what it’s prefer to be an individual with actual feelings.

Likable characters belong in romantic comedies and kids’s movies, not in tales the place grief eats you alive from the within out.

JJ: Luke, against this, is extra passive. How did you steadiness these two parental figures in shaping the emotional stakes?

AA: Luke’s passivity is a unique type of violence. He’s not storming via the home, breaking issues. He’s simply… probably not current. He’s exhausting to pin down. He’s passive, however he’s not apathetic.

I feel Luke represents concern—particularly, how concern can management us. Similar as grief, proper? However in his case, it’s a concern of confrontation. He’s afraid to step in and say, “This must cease,” as a result of if he does, he may lose Isla utterly.

Isla may be spiraling, however Luke’s silence is what offers that spiral room to develop. The actual horror comes from watching two folks fail one another in solely other ways and realizing that each failures are deadly.

JJ: Every youngster within the Hansen household has their very own voice. What was your course of in crafting distinct views, particularly from youthful characters?

AA: I really like writing youngsters, however writing from their standpoint may be difficult. Because the mom of a seven-year-old, I’ve seen firsthand how drastically a toddler’s worldview can shift.

My son at three, at 5, and now at seven? Utterly completely different folks. If I wrote from every of these views, I’d find yourself with three solely completely different characters. And that was my strategy.

I centered on age first—what every child would care about, what they’d concern, what would really feel large to them—and leaned into that.

But additionally, children are bizarre little creatures with their very own unusual logic, and I wished to honor that. They don’t speak like adults. They don’t assume like adults. Their fears are completely different, their conclusions are sometimes wildly mistaken, and their internal monologues can swing from SpongeBob to loss of life in three seconds flat. (Which, truthfully, is a part of the enjoyable.)

That’s what I saved coming again to—that every Hansen child wanted to really feel like they have been residing in their very own model of actuality. As a result of that’s how children survive chaos. Some go quiet. Some act out. Some attempt to make sense of it the one approach they know the way—via tales and video games and magical pondering.

I didn’t need them to really feel like aspect characters in a horror film. The children on this ebook actually inform the story greatest.

JJ: Grief performs a central function within the story however it’s layered with dread and speculative horror. Do you see emotional trauma as the final word horror?

AA: Completely. Isla doesn’t simply get up in the future and immediately crumble. She’s already carrying baggage from her personal childhood. A fractured, painful relationship together with her mom has left her with no actual blueprint for learn how to course of loss—and even learn how to be a mom herself.

Up till now, she’s taken all of that ache and used it to gas a determined try to be a greater mother. And he or she is an efficient mother… proper up till the second she isn’t.

Dropping one other youngster breaks one thing inside her. And this time, as an alternative of therapeutic, that fracture mutates. She turns into obsessive, unstable, and emotionally poisonous. That wreckage is what opens the door to Rowan wreaking havoc on the Hansens. He may appear to be the horror, however he’s simply the symptom. The actual illness is the emotional rot that’s been festering beneath the floor for years.

That’s what pursuits me most, and it’s a theme that comes up in my books many times—not the monster below the mattress, however the one sitting throughout from you on the dinner desk.

JJ: The thought of welcoming the “unseen” or the unknown into the house is so unsettling. What does that idea imply to you personally?

AA: For me, the “unseen” is what slips in when nobody’s paying consideration, invited via grief, denial, and silence. As a result of, as everyone knows, emotional wounds—if left open lengthy sufficient—begin to fester. And once they do, one thing at all times finds a solution to worm its approach inside.

In The Unseen, that one thing is a wierd, silent boy. However the true horror isn’t simply that he exists—it’s that the household is just too fractured to speak their emotions to at least one one other.

The adults are too preoccupied by their very own feelings to understand and even acknowledge the hazard. The invitation is rarely spoken aloud, however it’s additionally by no means revoked.

It’s written within the issues the Hansens don’t say to at least one one other, and by the point anybody notices that, yeah, one thing is significantly off, it’s already too late. Rowan has already made himself at residence.

That’s the type of horror that will get below my pores and skin. Not the factor outdoors, knocking—however the factor already inside, listening.

JJ: How did you determine on the Colorado setting? Did the agricultural isolation assist form the story’s tone?

AA: I grew up within the southwestern United States, and Colorado simply felt proper. It gave me the quiet I wanted—the massive skies and dry air. There’s a skinny, breathless ambiance on the market that feels prefer it holds an electrical cost. You’re at all times conscious of how small you’re in the midst of all that area.

JJ: You’ve written many various kinds of horror. How would you describe the place The Unseen sits inside your physique of labor?

AA: I truthfully don’t know the place this sits in my physique of labor. I simply write no matter’s at the moment residing inside my mind… or festering may be the higher phrase.

All the pieces I write is much less about what’s within the woods and extra about what’s below your pores and skin. I not often write something that may very well be thought of a slasher. I’m not significantly nice at bounce scares. There’s by no means a ultimate lady.

My work tends to dwell within the realm of sluggish unravelings—in threats the characters let in themselves as a result of it appears like hope as an alternative of horror.

I’ve at all times cherished horror that leaves you just a bit emotionally wrecked. The sort that lingers lengthy after the final web page as a result of some a part of it felt uncomfortably true.

JJ: The ending left many readers shaken and with lingering questions. Did you at all times know the way it could finish?

AA: I imply, sure and no. It’s no secret that my books are inclined to have brutal endings, so I knew it wasn’t going to be fairly. I had a basic sense of the place it was headed—nowhere good—however the ultimate few chapters fashioned organically.

I wished all the things to begin folding in on itself. Interwoven in a approach that, at a sure level, all you may assume is Oh noand preserve studying. It’s like a fuse that’s been lit, and also you’re simply ready for the growth.

And naturally, I by no means tie issues up with a neat little bow. The Unseen is about harm that doesn’t go away simply because the story ends.

JJ: Now that The Unseen is about to be launched, what do you hope readers carry with them after ending the ultimate web page?

AA: I hope they carry a way of unease they will’t fairly shake. That feeling like one thing’s simply barely off. Like possibly they left a door open. Like possibly they need to go verify on the youngsters, however not too intently.

This isn’t a consolation learn. It’s for the oldsters who need the dread to linger. And if The Unseen sticks with readers not due to what jumped out, however due to what was at all times there, quietly ready, I depend that as a win.

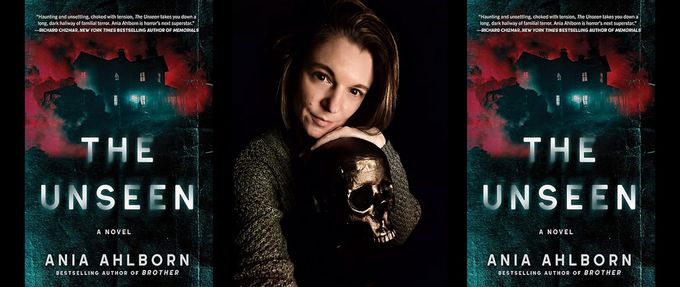

Featured picture: Aniaahlborn.com