In 2018, the curator Catherine Taft started researching an exhibition on ecofeminism, assuming it might be a retrospective on a philosophy that had fallen out of trend. Ecofeminism emerged from environmental, feminist, social justice and antinuclear activism within the Seventies.

The motion resists conventional techniques of patriarchy and capitalism that it contends subjugate girls and exploit nature. It advocates for embracing collaboration, recognizing humanity’s dependence on ecosystems and respecting all life as sacred.

However within the Nineteen Nineties, critics accused ecofeminism of stereotyping and falsely equating girls and nature. The backlash brought about the motion to go dormant. Then Taft observed a shift. The COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests shined a light-weight on social and environmental justice, resulting in a re-emergence of ecofeminism.

“Persons are utilizing the time period once more and are excited to embrace ecofeminism as an method,” Taft, deputy director of the Brick gallery in Los Angeles, stated in a video interview. Consequently, she centered the present on the current and future, and reframed ecofeminism “as an expansive technique for survival in twenty first century life,” she stated.

Taft’s exhibition, “Life on Earth,” opened Feb. 28 in The Hague, Netherlands. On the similar time, TEFAF Maastricht’s Focus initiative is showcasing two historic and up to date ecofeminist artists. Collectively, these reveals illuminate the numerous aspects of this evolving motion.

Juliana Seraphim

Contemporary from bringing an ecofeminist exhibition to Frieze London 2024, Richard Saltoun Gallery is dedicating a TEFAF Maastricht present to the surrealist artist Juliana Seraphim, referred to of their information launch as “an early pioneer of up to date ecofeminist discourse.” Born in 1934 in Jaffa in southern Tel Aviv, Seraphim fled to Lebanon when the 1948 Arab-Israeli Struggle broke out. As a painter, she was criticized by her fellow Palestinian artists for not addressing their trigger.

“Juliana was way more centered on girls’s liberation,” stated Niamh Coghlan, director of Richard Saltoun Gallery, in a video interview. “She felt that ladies have been essentially the most lovely varieties and essentially the most delicate, empathetic creatures on Earth. That was what she needed to color.”

Seraphim, who died in 2005, noticed a world marred by wars, inequalities, harsh residing circumstances and heartless social interactions. She needed to point out individuals what she referred to as “a lady’s world,” infused with love, magnificence, sensitivity and entanglement with nature.

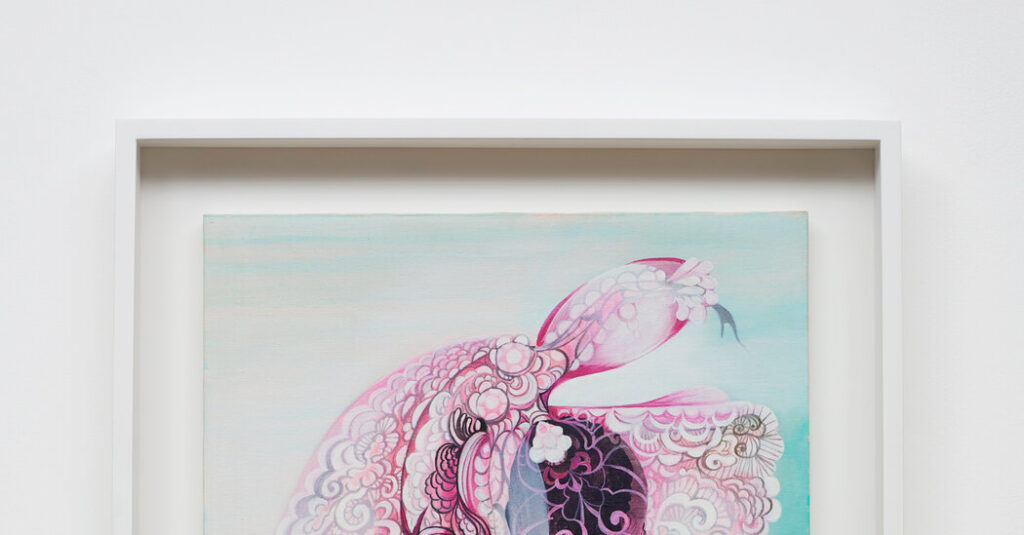

In her work “The Eye,” Seraphim painted girls sporting insect wings and diaphanous clothes laced with capillaries, gliding by means of buildings resembling stone hoodoos. “Dance of Love” portrays sunken machines and buildings beneath a feminine type triumphantly springing from a flower amid pink swirls and a stylized snake. In “Flower Lady,” a sphinxlike girl’s head envelops petals and a seahorse, whereas butterfly wings cascade down her again and blossoms fill her breast. All three works are included within the Maastricht present.

“You possibly can see her enjoying with the best way that the setting is the human physique,” Coghlan stated. “We’ve made a divisive level of claiming that people and the pure world are very totally different. However they’re the identical factor. Juliana was occupied with pulling them again collectively.”

Gjertrud Hals

When the Norwegian fiber artist Gjertrud Hals casts about for inspiration, her thoughts catches components of ladies’s tradition and the environmental destruction she has witnessed. Rising up on the distant island of Finnoya, within the Nineteen Fifties, she witnessed the overfishing that collapsed the inhabitants of fish and whales, forcing many households, together with hers, to go away Finnoya.

Whereas residing within the Norwegian fjords, Hals watched as a spectacular close by waterfall was captured for hydropower. A yr later, she and her husband launched a profitable marketing campaign to save lots of a watershed from being dammed. Concurrently, the feminist marches of the Sixties and the associated push to raise girls’s crafts to advantageous artwork motivated Hals to study weaving and embroider feminist quotes.

As we speak, Hals stated she is much less political. However ecofeminist themes will subtly saturate her solo exhibition at TEFAF, introduced by Galerie Maria Wettergren. Her fishnetlike paper vessels conjure the shapes of seashells and wombs whereas honoring the female custom of fiber arts and talking not directly of womanhood and nature. “On one hand, they’re susceptible; alternatively, they’re robust,” Hals stated in a video interview.

In a nod to people’ interconnectivity with nature, Hals muddles the pure and the human made. She customary footwear from roots and molded Japanese mulberry bark paper into small human heads, which she’s going to show amongst similar-looking mushrooms plucked from bushes.

In “Golden,” a copper internet weaving has “caught” golden herrings and different animals that Hals reduce out from the insides of Norwegian caviar mayonnaise tubes, maybe questioning the worth positioned on the residing world. In “After the Storm,” shells and pearls appear to have washed up right into a wire internet, providing a hopeful message. “We’re in a political scenario increasingly, not solely in Norway however in Europe and customarily,” Hals defined. “And we hope that someday there might be a time after the storm.”

Life on Earth

In curating “Life on Earth: Artwork and Ecofeminism” — which debuted final fall on the Brick in Los Angeles and is on present at West Den Haag museum in The Hague by means of July 27 — Taft aimed to painting ecofeminism as an intersectional motion. She additionally needed to encourage hope amid a number of planetary crises. “A part of my work is to point out that working collectively and discovering communities the place you can also make a change actually does make a distinction,” she stated.

As such, a 24-hour on-line/in-person symposium on ecofeminist artwork will accompany the present on March 21. It’s going to comply with the solar from the Loop gallery in Seoul to West Den Haag to the Brick, encompassing communities of contributors across the globe. At West Den Haag, the exhibition will characteristic practically 20 artists from Colombia, Nigeria and different international locations, a lot of whom merge eco-friendly life with their artwork.

The artwork collective Institute of Queer Ecology presents movies of caterpillar chrysalises to examine how capitalist extractivism — depleting nature and exploiting human labor to maximise revenue — might be reconstituted, butterflylike, right into a regenerative system. The artist Yo-E Ryou created a soundscape and underwater maps that chronicle her expertise studying sustainable seafood harvesting from the feminine free divers of Jeju Island, South Korea.

Leslie Labowitz-Starus’s set up grew out of her 40-year art-life ecofeminist undertaking, “Sproutime,” which blends a sprout-growing enterprise, training at a farmers market, efficiency artwork and installations. At West Den Haag, she juxtaposes sprouts, soil and posters from girls’s peace marches for example how warfare destroys and contaminates soil, resulting in meals insecurity.

The present offers viewers “openings to take a look at the world from a feminist perspective, which is about care, nurturing and never being aggressive,” Labowitz-Starus stated in a video interview. “We’re saying there’s one other approach to be on this planet, and our consciousness has to evolve.”