I grew to become a one-way pen pal for democracy in 2018, writing letters and postcards to strangers within the lead-up to that 12 months’s midterm elections.

I had spent the months earlier than marching for ladies, science, immigrants and Muslims. Then I made a decision marching wasn’t sufficient. I wanted to have interaction particular person Individuals about electing politicians who shared my values.

In order that September, I attended a grassroots occasion to find out about volunteer voter outreach hosted by a Los Angeles group referred to as Civic Sundays. We might select to learn to knock on doorways, name and textual content potential voters or write postcards to have interaction folks.

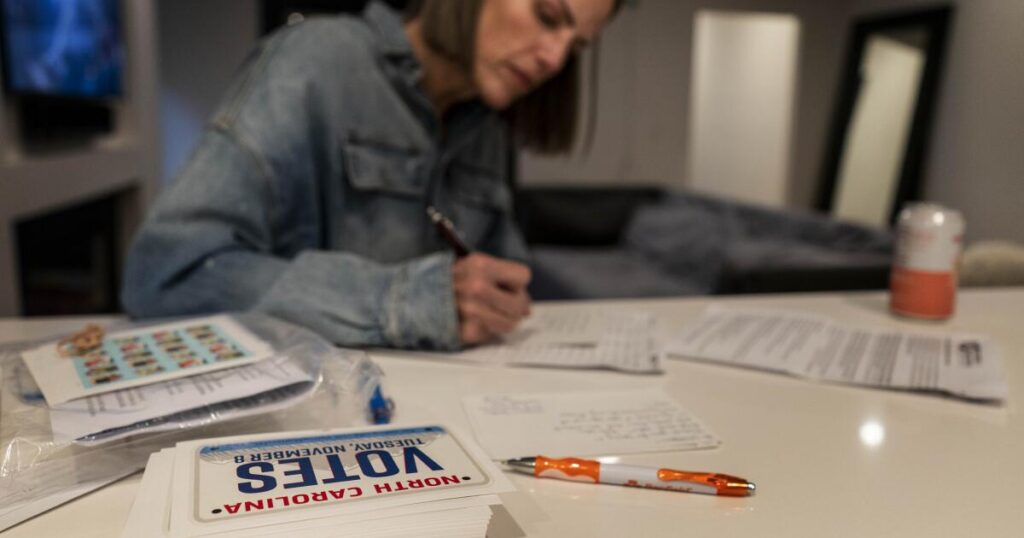

I’d by no means heard of writing postcards to strangers as a solution to encourage them to vote. However I used to be charmed by the considered an analog technique of saving democracy. Civic Sundays and different organizations, lots of which sprang to life following the 2016 presidential election, provide volunteers with lists of names and addresses of registered voters. The writers provide penmanship, stamps and typically the postcards themselves.

I joined a big desk of individuals with seemingly professional-level glitter and Magic Marker expertise. Whereas their postcards regarded like illuminated manuscripts, I painstakingly struggled to make mine legible. A fourth-grade instructor as soon as instructed me my writing resembled a hostage taker’s ransom notice, however fortuitously, I didn’t need to take a handwriting take a look at to get a seat on the postcard desk (some organizations do truly require one).

I discovered the work quite healthful, however I wasn’t bought on the concept of making an attempt to have interaction a inhabitants that couldn’t be bothered to vote.

The extra postcards I wrote, the extra I began to surprise: Who have been these rare voters? Why weren’t they doing their civic obligation? If I regarded their deal with up on Google Maps, what would I see? Unmown lawns? Gated mansions?

I grew to become racked by a need to know who precisely have been these shirkers of civic duty. However we’d been given clear directions: Don’t personally have interaction the recipients of your missives. As an alternative, we adopted a transparent and concise script of just some sentences.

I participated in one other postcard-writing marketing campaign for the 2020 presidential election. This time, I particularly requested names from a swing state, Michigan. As I wrote to those strangers, I grew to become more and more pissed off, imagining them having fun with their weekends with no scintilla of voting guilt whereas I agonized over whether or not they may be offended by a postage stamp with a cat on it.

Once I talked about these frustrations to a cynical pal, he instructed me to learn the Trappist monk Thomas Merton’s well-known 1966 “Letter to a Young Activist.” I ought to have been suspicious, seeing as my pal can be the final particular person to put in writing a postcard to a stranger. Certain sufficient, Merton’s phrases didn’t reassure me in regards to the destiny of my postcards. “[D]o not rely upon the hope of outcomes,” he wrote. “If you find yourself doing the form of work you’ve taken on, primarily an apostolic work, you will have to face the truth that your work can be apparently nugatory and even obtain no outcome in any respect, if not maybe outcomes reverse to what you anticipate.”

After studying Merton’s letter, I spent some months not writing the scofflaw voters of Michigan, Georgia, Arizona or anyplace else.

However when the 2024 election marketing campaign began up, with the way forward for the nation as soon as once more on the poll, I requested for one more postcard record.

This time one of many decisions was to put in writing to folks in my very own state, California. This felt extra like writing a neighbor than somebody distant and completely unknown. As soon as I had my record and began studying the names and addresses, I noticed a few of my postcards can be going to individuals who lived close to the city the place I work.

After which it occurred. I acknowledged a reputation. The Gen Zer who wanted a nudge to vote was one in every of my considerate, succesful college students.

I lastly had a solution in regards to the folks I used to be writing to. They have been identical to the remainder of us: single singles and matriarchs of massive households, individuals who drive electrical vehicles and individuals who drive massive vans, charming folks and worsening folks and neighbors who performed their music too loud however have been candy with their children. Folks so busy main their lives they often forgot or opted to not vote.

Recognizing only one title made me sure I needed to hold penning these epistles of democracy, to maintain reminding others, even when they didn’t pay attention or wish to hear it, that their vote mattered. With new perception into Merton’s well-known missive, I needed to put my belief in, as he put it, “the worth, the rightness, the reality of the work itself.”

Melissa Wall is a professor of journalism at Cal State Northridge who research citizen participation within the information. This text was produced in partnership with Zócalo Public Sq..